SEVEN DAYS IN SPORT: The Demons have done it for Robbie at last – at the second attempt, writes RON REED.

ROBBIE Flower and Jim Stynes would have been the proudest men in footy Heaven when the drought broke. The Demons of 2021 said they were doing it for these two old champions, along with several other club identities who had died far too early. As has been endlessly documented, the oldest footy club in the land had been waiting since 1964 for this euphoric moment of deliverance, enduring the pain of two heavy Grand Final defeats in 1988 and 2000. But if Flower and Stynes were still around to be asked which of the many seasons of disappointment and frustration resonated the most they would probably, I think, nominate 1987.

That was the year they lost the Preliminary Final to Hawthorn by two points in hugely dramatic circumstances, with Hawk Gary Buckenara converting a free kick into the winning goal after the siren, helped by the young Stynes – still largely unschooled in the rules of a game he had not grown up with in Ireland – giving away a 15 metre penalty by running across the mark.

It was Flower’s 272nd and last game of a stupendous career – then a club record – and Stynes’ unlucky 13th in the first year of what also became a long and memorable contribution of 264 appearances.

Flower’s agony was physical as well as emotional – after missing the mid-season night premiership with a broken finger, he then played throughout the finals with another one, and had to leave the field early against the Hawks after having his shoulder put out of commission by a heavy hit from the rampaging Robert Dipierdomenico, only to be forced to return to the fray when someone else went down in the white heat of the final quarter.

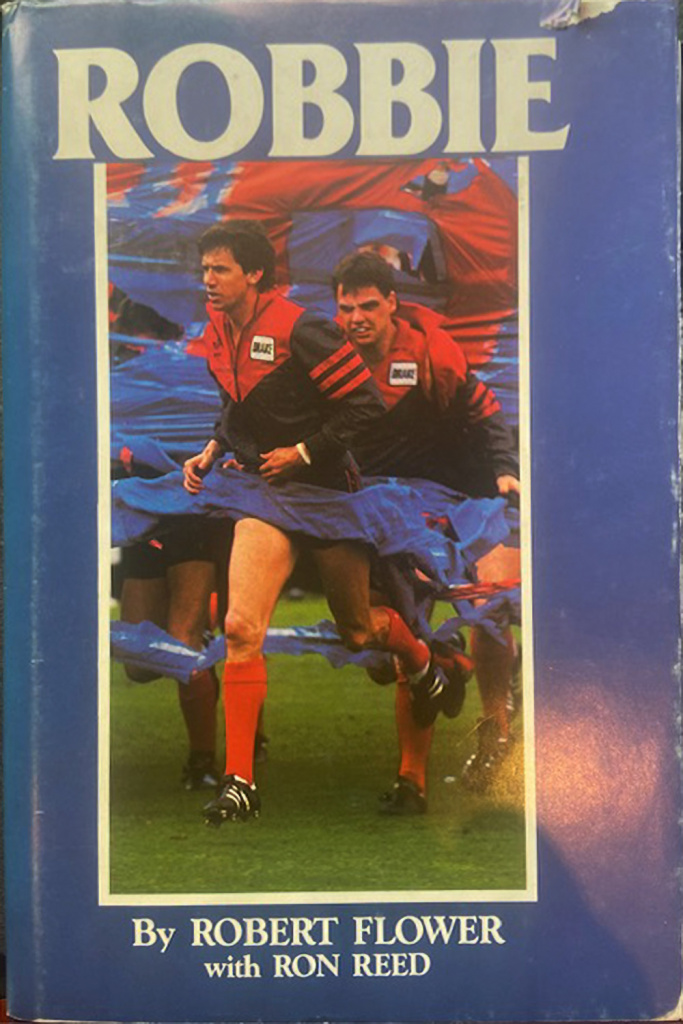

I watched all this from a privileged vantage point, having spent the entire season working closely with Flower on a book about his career. Titled simply ROBBIE, it was mostly a “ghosted” autobiography, but amplified by my own observations of his incredible impact on that finals series – and why it meant so much to the club.

The Demons were in disarray on and off the field, having finished second last – propped up only by the also perennially unsuccessful St Kilda – for the previous two seasons, and Flower decided he had had enough and would retire.

Desperate for something to hang their hat on, and to twist his arm to go around one more time, the club dedicated 1987 to collectively “do it for Robbie,” to give their favourite son his first – and only – opportunity to play finals footy. By the skin of their teeth, they got there. His brilliant performances over the next three weeks combined with the heart-breaking denouement added up to one of the more captivating stories in the game’s long history, which made the book something of a best-seller. To many Demons fans, it is still a collectors’ item.

On the Monday morning after the match, I rang to see how he was feeling, which was probably a silly question in one sense but an important one to bring closure to our project.

Our conversation was captured by this poignant piece I wrote for the The Herald newspaper that day:

NOW, HE SAYS, IT’S TIME TO GO

“IT WAS not,” Robbie Flower said wearily, “the way I would have wanted to finish.” In terms of understating the case, it was a bit like suggesting the Preliminary Final had been quite interesting. The Melbourne skipper was still feeling the pain of it all, physically and emotionally. He was off to see a specialist about the shoulder that buckled under a full-frontal but perfectly fair assault from the Big Dipper midway through the second quarter.

“I can’t lift my arm,” he said. “It’s very painful.” So, the truth is that if Melbourne had survived that desperately disappointing climax on Saturday, football’s ultimate irony would have been at hand. Flower almost certainly would not have been able to play in the Grand Final. Having done it for Robbie, as the entire club set out to do almost 12 long months ago, the Demons would have had to enter the premiership play-off without him. Four months ago they had made the final of the night competition, and won it – and, tragically, Flower missed that, too. He had a broken finger.

He had a broken finger, a different one, for the past three weeks. It had to be pumped full of painkillers each training night and before each game. “I’ve been feeling like a pin-cushion,” he said. And now the shoulder. He wasn’t even sure now what was wrong with it, but he knew this much for certain: the injuries are coming along altogether too frequently now. It’s time to go. He suspected that last season, he’s known it for most of this season.

With five goals against North Melbourne in the Elimination Final and four against Sydney in the first semi, interspersed with a series of inspirational marks, he has proved beyond argument that, at 32, his capacity to make an impact on any game remains formidable. It is why John Northey said to him on Saturday night that he wanted to have a chat at some quiet moment during the forthcoming promotional trip to Canada. The coach – for the first time this year – will be wasting his breath. “I can’t see anything changing my mind,” said the skipper. “I’ve retired.”

Flower remains both proud and grateful that after 15 years and a club record of 272 games he at least got the opportunity to play in a final.

As the club – players, trainers, officials and families – gathered to grieve at a function at VFL Park on Saturday night, he stood up and said so. “I thank everyone for that chance,” he told them. They should have been thanking him, of course, and no doubt that will be done fully and appropriately at the right moment. For the grace and style that he brought to the game, for the loyalty he maintained to the club during endless grim years, for his determination to be true to such ethics as sportsmanship and fair play, he deserves far more than to trudge off in ashen-faced despair, as he was forced to do on Saturday.

“Life has to go on,” he said. “If you can learn something like that, you’re better for it.” There was no bitterness about the umpiring decisions that cost Melbourne its moment of glory. “That’s football,” he said.

None of that, though, disguised the lingering agony. In the dressing-rooms seconds after that long, long siren finally stopped wailing, it was difficult to believe that a game, a sport, could produce quite such a scene of utter desolation. It was impossible to imagine that anything could be worse. It could, said Flower. “When I went home to bed and thought about it, it hit me even harder.”

He had watched the dying moments from the other end of the ground, standing there with his peer, friend and rival, Hawk skipper Michael Tuck. When Buckenara was awarded that fateful free kick, he shook Tuck’s hand and said: “It’s you or us. I hope it’s us, but all the best.” Then came the climactic 15m penalty. “That removed all doubt,” said Flower. “I sprinted for the race, paused to watch the goal go through and was first – and saddest – in.”

The reception awaiting him and his shattered team-mates was, initially, thunderous. Northey was beside himself with rage. As the big Irishman Jim Stynes, perpetrator of the fatal error, arrived, Northey bellowed across the room at him: “Don’t you ever do that again, Jim!”

Then he paced up and down, a can of soft drink in his hand, swearing loudly at the team. At least one of them – Simon Eishold, who had missed a chance to kick the winning goal – was in tears. The gist of Northey’s message was that they had learned a lesson the hard way, missed the chance of a lifetime. He stormed into the toilet, almost de-hinging the door, and returned within seconds. “Take a picture and piss off,” he bellowed at a bank of photographers.

And then Northey ordered everyone out. “Things didn’t improve much,” Flower reported later. It was a graphic portrait of a man close to breaking point under the sheer weight of crushing disappointment. But he is a strong man, John Northey. He has proved that this year, this month. He proved it again. He recovered his composure and went through the endless, obligatory media interviews. And he made no excuses.

Neither, in the end, did Robbie Flower. Melbourne’s riveting influence on football’s showpiece month transformed an entirely predictable two-horse contest into an utterly unforgettable drama of many parts, and there were several reasons for it. By far the most important was the quality of leadership.

Embed from Getty Images· Robbie Flower died seven years ago this weekend, October 2, 2014.

· Jim Stynes died on March 20, 2012. The last time I saw him personally was not all that long before that when I was exiting Parliament station at peak hour and heard my name called. It was big Jim, then the Melbourne president, rattling tins and requesting a donation from me and everybody else who walked past. I forget whether it was for the club or his children’s charity, but I was struck that someone in his lofty position would be doing the basic hard yards like that – but it helped explain why he was admired so much.

· Flower and Stynes were the two most prominent in a lengthy list of prematurely lost club identities to whom the Dees dedicated their premiership – but there was no mention of Max Walker, who died at just 68 five years ago this week. Big Max was better known as a Test cricketer of course, but he was a substantial contributor to the Dees, playing 85 games.

RON REED has spent more than 50 years as a sportswriter or sports editor, mainly at The Herald and Herald Sun. He has covered just about every sport at local, national and international level, including multiple assignments at the Olympic and Commonwealth games, cricket tours, the Tour de France, America’s Cup yachting, tennis and golf majors and world title fights.

Discussion about this post