SEVEN DAYS IN SPORT: Joe Root will be a welcome arrival for the Ashes while a ruthless predecessor is again under scrutiny nearly 100 years after his successful but ill-starred campaign, writes RON REED.

CAPTAINS of the England cricket team haven’t always been made as welcome as they might be when they arrive to play for the Ashes, none more so than the mastermind of the acrimonious Bodyline series in 1932-33, Douglas Jardine. But that won’t be the case with Joe Root this time around. He probably should get a standing ovation when he walks out to toss for the first Test at the Gabba next month, because it appears that he has been more responsible than anyone for shutting down any thought that the tour might not go ahead because of the difficulties of dealing with the covid restrictions on the team and their families. That was never likely, only ever a bit of sabre-rattling in order to ensure the arrangements were as satisfactory as possible, but thanks to Root’s leadership it seems the summer will proceed with maximum positivity and minimum complaint – and that’s a very good thing.

What Jardine’s elderly ghost would make of that is anyone’s guess, but for anyone so inclined to guess, erudite help is at hand. The most unpopular captain in the game’s history and the deeply controversial win-at-any-cost strategy he employed have raised their ugly heads again just in time for another pursuit of the little old urn he was so determined to retrieve from what he regarded as an upstart colony.

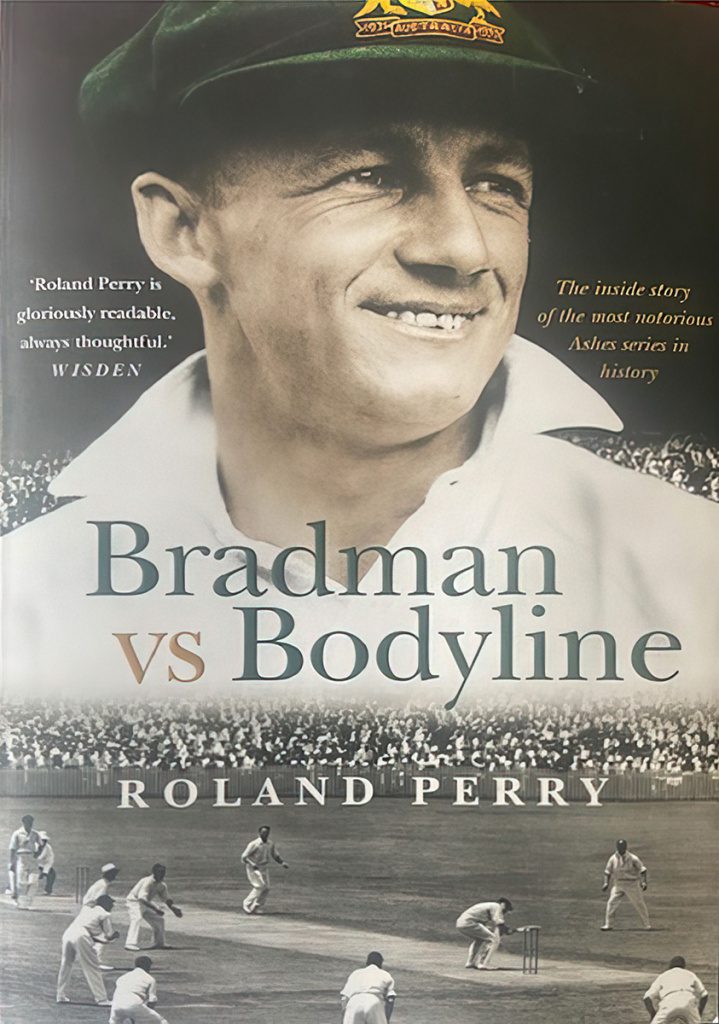

Prolific author Roland Perry’s 37th book, Bradman vs Bodyline, is by no means the first account of that traumatic summer but it does claim to be the definitive one, “compelling, extensively researched and full of new insights,” according to the publisher, Allen & Unwin. Certainly, it greatly broadened my education on the topic, particularly on what made Jardine and his star fast bowler Harold Larwood – with their vastly different backgrounds, personalities, schooling, social and professional status and attitudes towards both sport and life – able to harness a mutual antipathy and probably jealousy towards the best cricketer of their time, or any other time, the young Don Bradman. They seldom referred to him by name, rather “the little bastard,” Perry writes.

It is a well-known matter of record that they set out to physically intimidate him, and the rest of the Australian batsmen, by bowling at his body and head with an arc of close leg-side fielders waiting for panicked catches to eventuate, and if he or anyone else got hurt, bad luck. It worked to an extent, limiting Bradman’s average by about half to 56.57, still the best of any batsman on either side, and the tourists won the series 4-1. To Jardine, the ends justified the means, but it generated outrage in Australia and considerable uneasiness in England, and badly damaged the relationship between the two countries.

Ever since, Jardine has been almost like a pantomime villain in the annals of Australia’s sporting history, unlike Larwood, who eventually emigrated to Sydney and discovered, to his surprise, that there was no lingering dislike or disrespect for him.

But few modern sports fans, I suspect, would be capable of analysing him much beyond that, as Perry has done at length, possibly with considerable help from Bradman, with whom he had a strong working relationship – this is his sixth book about him and 10th about cricket.

He also directly quotes a lot of Jardine’s conversations and instructional utterances and others talking about him in his absence, which – given this all happened nearly 100 years ago — is either a masterpiece of research or a little literary licence. Either way, it is insightful, fascinating in fact.

Jardine, he says, was a Jekyll and Hyde personality who had his positive points. His vice-captain Bob Wyatt said he could be “insufferably offensive.” Perry adds: “There were frequent spontaneous displays of invective in front of other team members that left the victim numb and humiliated.

“Jardine also showed a ‘cold air of disdain’ for anyone who crossed him or let him down, with the bat, bowling, behind the wicket or in slack fielding. He had a lack of empathy in regard to those under him. He showed scant regard for other’s feelings. It was very much the way of the military, which underpinned the British Empire, but it did not have to apply so rigidly to sport.

“It was as though he didn’t understand the impact of his emotional outbursts and didn’t think they could offend in any meaningful way.”

Embed from Getty ImagesAt least, Perry says, he didn’t hold grudges, even though he could be vindictive.

Opinions did differ.

Larwood never had a bad word to say about him and was forever loyal despite being treated “cruelly” at times, while other players were divided in their assessments. One, spin bowler Hedley Verity, named his son after him.

Jardine paid a sad price for carrying “the stigma of Bodyline” into retirement, where he attempted unsuccessfully to make a living writing books and articles about cricket while working as a bank clerk, and was forced at one stage to earn money from playing bridge before eventually being wounded while serving at Dunkirk during the war.

Perry reports that the cricket bible, Wisden, which had been an effusive supporter, did not bother to write an article about him when he retired. “It was the ultimate snub, and it hurt the proud Scot.”

When he died prematurely of lung cancer at 57 in 1958, Bradman refused to comment publicly, which, pointedly, was not the case much later when Larwood passed at 90. “(He) will live in history as one of the greatest bowlers of all time,” he said, although without elaboration of any sort.

Bradman did not want to say anything derogatory about Jardine so he said nothing — but, says Perry, he could never forgive him for the damage he had wreaked on the game and for his efforts to destroy him.

“With time, and as memories of adversaries faded, Jardine has come to be seen in a better light. Some commentators with obvious motives and others have revived and complemented his memory and image as a ruthless yet outstanding tactician. Only Dr Jekyll is seen now,” Perry writes.

As for Bodyline, it was theoretically banned in 1934 but never actually outlawed until the laws were changed in 1957 so that only two fielders were allowed behind square leg, close to the batsman or not. In the 90s, bowlers were limited to two short balls an over.

But, says Perry, referring to the death of Australian Test player Philip Hughes and other frightening incidences of batsmen being hit and injured, “it’s reinventions within the laws are as dangerous as ever.

“While Bodyline no longer exists, its intention to intimidate and if necessary bruise a batsman into submission or a mis-stroke in self-defence remains. Even with the law and body protection that the Bradman era did not have, batsmen facing the fast men of the modern era will have to show as much courage and skill as their predecessors.”

BRADMAN v BODYLINE, by ROLAND PERRY, PUBLISHED BY ALLEN & UNWIN, RRP $32.99.

RON REED has spent more than 50 years as a sportswriter or sports editor, mainly at The Herald and Herald Sun. He has covered just about every sport at local, national and international level, including multiple assignments at the Olympic and Commonwealth games, cricket tours, the Tour de France, America’s Cup yachting, tennis and golf majors and world title fights.

Discussion about this post