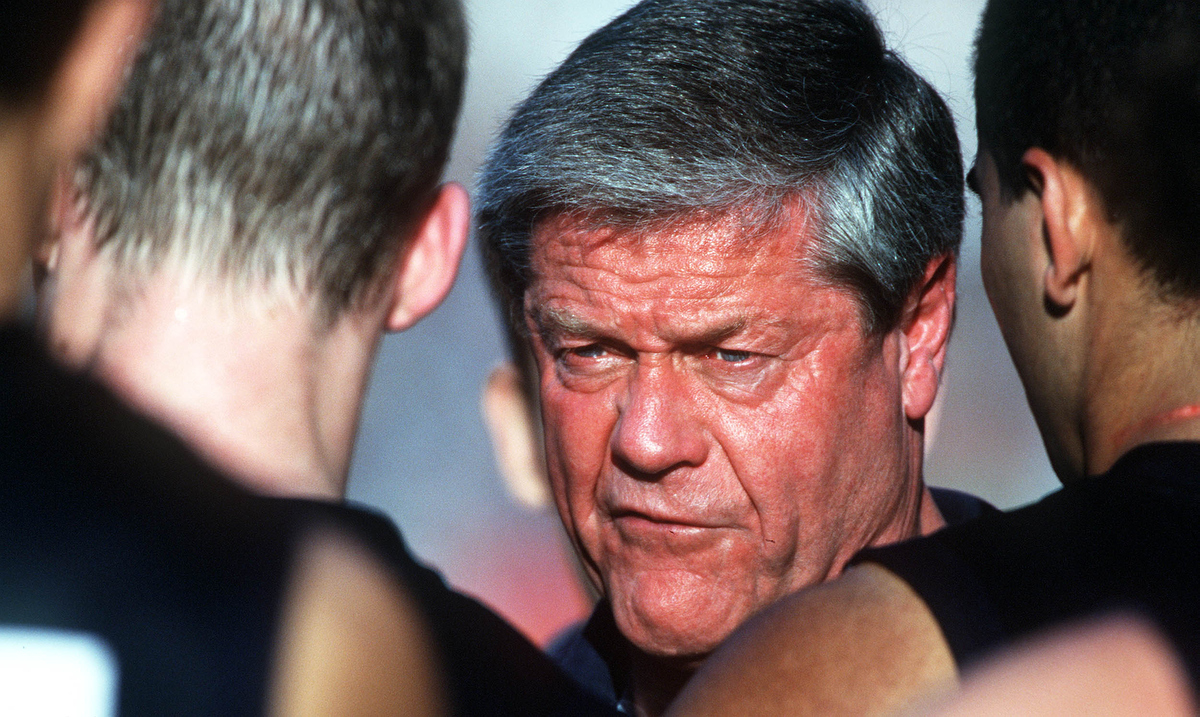

COACHES USUALLY get the credit for masterminding any premiership win but that wasn’t quite the case the last time Carlton saluted, writes RON REED:

DAVID PARKIN coached Carlton to three premierships and Hawthorn to one and it goes without saying that he is proud of them all, but one stands out. In 1995 the Blues lost only two games on the way to the Grand Final, where they thrashed Geelong by 10 goals. A coaching masterclass? Well, not necessarily – Parkin had less say in the way the season played out than any coach before or since, and that goes not just for footy but every Australian sport, he believes.

It was all about player power in a way that had never been attempted or permitted before, Parkin told guests at the lunch another former Carlton coach, Percy Jones, hosts at the North Fitzroy Arms pub every odd-numbered Friday. The players – led by Steven Kernahan, “the best leader I have ever been associated with” – picked the team every week, decided the tactics and match-ups and laid down the disciplinary rules and the punishments for breaching them.

This radical approach succeeded spectacularly well – but that doesn’t mean it would have worked for any other team at any other time, Parkin said. It certainly wasn’t replicated at Carlton – the Blues have never won another flag.

So how did it come about? Parkin believes he had the best team in the competition the two previous years, but couldn’t get the job done. They finished second on the ladder both times, losing the Grand Final to Essendon inn 1993 and the second semi to Geelong in 1994. An in-depth review followed. “It slaughtered me,” Parkin said. It identified 16 problems with the manner in which he was coaching the team. “It was hard to cop that,” he said.

“Technically and tactically we were OK, physically we were good, but psychologically there was something wrong.” The players asked for a sports psychiatrist to be employed, which was another slap for the coach, who has always worked as an educator specialising in sports science. So they poached one from his old club, Hawthorn, a bloke named Anthony Stewart, who had also worked with the Australian cricket and netball teams.

One of the upshots – a highly surprising move from a coach who describes himself as “the most autocratic, dictatorial prick ever” – was that a group of 15 senior players were allowed to take ownership of selection and tactics. “It would not have happened before or since in Australian sport, full stop, not just footy,” Parkin said. “They were committed, competent people and no other club had that many such players.” When the list was first pinned up on the wall outside the coach’s office, Parkin became aware that the entire team gathered around it “like bees at a honeypot”. Then two knocked on his door, one after the other.

The first was veteran on-baller Barry Mitchell, who asked to be removed from it because he had been injured and did not feel part of the group. He was told, OK, but when he was fit he would be expected to join in. The two shook hands and Mitchell left. “Next thing, the door bursts open and in comes this bespectacled landscape gardener, who I’d never heard speak before,” Parkin said. “It was Brett Ratten, who demanded to know how you got into that group. I told him you got invited. ‘Well, why wasn’t I invited?’ Because you’re an 18-year-old back pocket player, tuppence a dozen. ‘I think about the game better than half those blokes, I understand the game better than anybody, I have to be in the group.’ I told him, ‘Yes, I think you should,’ so he replaced Mitchell. To this day, he is the most thoughtful, thinking player I have ever had. He went from the back pocket to the midfield and won that year’s best and fairest. Brett was the bloke who led the way in the group, which most people, including me, had no idea he could do. He was a very special bloke.”

Ratten, of course, went on to coach the Blues for five and a half years before being controversially sacked to make way for Mick Malthouse five years ago, a decision Parkin describes as “a terrible error”.

The new ownership dynamic was put to the test late in the season when a defender was injured and Parkin asked the captain of the backline, Peter Dean, who they wanted to step up. Dean nominated a little-known fringe player, Troy Bond. The coach told him to “stop joking – who do you really want?” Told it was no joke, Parkin said he would never get it past the match committee. “That’s your problem,” said Dean, hanging up in his ear. Parkin: “I went to the match committee, said Troy Bond, and they all pissed themselves laughing. No, seriously – they want him. Who’s they? The back six. Who’s picking this team? Well, unbeknownst to you, they are. They looked at each other and then all stood up, walked out and resigned. I walked out and pleaded for them to come back. They decided to continue.

“Interestingly, Bond went on to play a role he had never done before, as a half-back, and within three weeks they had him playing like a German band. All of us – coaches and staff – had failed him and he was now doing all the things we thought he could when we recruited him.” However, when the Grand Final arrived, the players voted him out of the team again. According to another source, when he learned this Bond was so shattered he walked out without speaking to Parkin or any team-mate and did not attend the big match. “He blamed me,” Parkin said. Bond was cleared to Adelaide, where he played in the 1997 premiership and missed the 98 flag because of injury. “That made me feel better about it,” Parkin said.

Carlton won the Grand Final 21.15 (141) to Geelong’s 11.14 (80) largely on the back of a superb performance by Greg Williams, who kicked five goals from the centre and won the Norm Smith Medal for best afield. At a relatively recent fundraiser attended by many from that team, Williams was interviewed by former team-mate Adrian Gleeson, which Parkin anticipated would turn out to be a mistake because the dual Brownlow medallist was notoriously taciturn. Not this night. “I remember the game like it was yesterday,” Williams told Gleeson. “At the start of the game I looked down the back and saw Steve Silvagni lining up on Gary Ablett (senior) and thought, hell, I’d hate to have that job, fancy getting Ablett in a Grand Final. So I thought I’d better drop back and give him some support. I got a few handpasses around, knocked Ablett over and gave him one and thought, well, that’s under control, so I slipped back to the middle and picked up 42 very sharp ones between the arcs and kept pushing it into the forward 50. Do you think those blokes could do something with it? I got sick of it going down there and coming back so I slipped down and kicked five goals – so when you think about it, it’s no wonder I won the Norm Smith.” He got no argument there! Parkin: “Everyone was stunned – we didn’t think he could talk.”

Despite the magnitude of that season’s all-conquering performance, Parkin believes the group that won in 1981-82 – his first year at the club – were the most talented team he coached. Basically the same players had won in 1979 under Alex Jesaulenko, who then departed in one of the great political stoushes in footy history, and made the finals again in 1980 under Perc Jones. “They were as good as any of the great teams of the modern era but have not been recognised as such,” said Parkin, who made sure that message came across in last year’s best-selling book about the greatest Carlton era, Larrikins & Legends, by Sportshounds contributor Dan Eddy.

“They had such enormous individual talent they could run individually and make the team go,” Parkin said. “They were a pretty special group. The bond they had was as strong as any bond in any team I have been associated with. The sad thing is that so many people play in great teams without ever achieving the ultimate and they don’t have the same bond. Runners-up never meet. If you’re lucky enough to be in a team that succeeds together there’s a bond for life that can’t be broken. Carlton blokes do it as well if not better than any other club. There was a mateship there, second to none.”

The mateship surfaced in the 1982 play-off against Richmond. “I remember stopping the players in the race before they hit the ground. I just had this gut feeling, that the Richmond mentality, one of our little blokes would get belted in the first few minutes. I can talk about this now but I’m probably ashamed, in a sense, of what I said. I told them that if one of our little blokes gets knocked out I want you to turn around and knock out the bloke standing next to you, I don’t care who it is. They looked at me strangely and I thought that’s a pretty stupid thing to say.” Before long, Tiger ruckman Mark Lee – “big, brave Mark Lee” – ran through pint-sized rover Alex Marcou in a manner that disgusted Parkin. “They all ran to the incident except the back six, so I looked at the six to see who was ‘coachable’. Mario Bortolotto let one go from down here and hit David Cloke on the jaw, didn’t knock him out but sat him on his arse in the goalsquare. I can still see Mario standing over him and Cloke going, ‘What was that for?’ Mario said, ‘That’s for my little mate down there.’ Ever since that day I have taken Mario to lunch every year to thank him for being the most coachable player I had.”

RON REED has spent more than 50 years as a sportswriter or sports editor, mainly at The Herald and Herald Sun. He has covered just about every sport at local, national and international level, including multiple assignments at the Olympic and Commonwealth games, cricket tours, the Tour de France, America’s Cup yachting, tennis and golf majors and world title fights.

Discussion about this post