IT WAS the day of the Easter Monday Massacre. Two crafty Scots turn up at the Stawell Gift with underpants stuffed with cash and the bookmakers in their sights. JOHN CRAVEN recalls the colourful coup:

IT WASN’T hard to crash your way into the Melbourne Herald’s pokey third floor sports department in Flinders Street in the early 1980s. The only security was a poisonous fog of cigarette smoke generated by cricket scribe Rod Nicholson, the legendary golf and tennis writer Don Lawrence, and later on his replacement Peter Stone.

My desk was at the far end of the narrow-gutted room, and that suited me fine. I faced a blank concrete wall while I dealt with the stack of athletics, cycling, swimming, and VFA and VFL football jobs thrown at me by The Herald’s unflappable sports editor Ron “The Hound” Reed.

My relatively tranquil existence was broken early one morning in the week before Easter in 1981 when two exuberant fellows burst through the door and headed straight for me, tapping me on the shoulder.

“We’re from Scotland,” they beamed. “And we’re here to back George McNeill to win the Stawell Gift.”

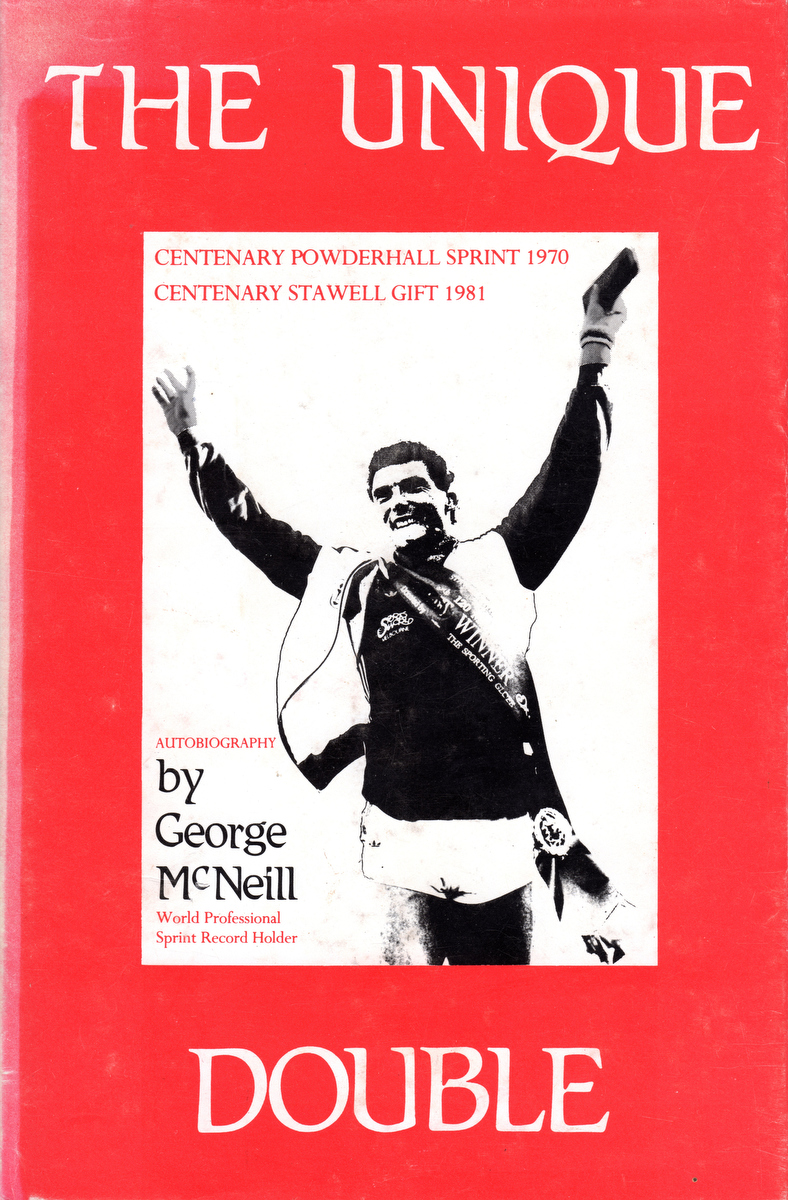

I was unimpressed. McNeill, the former semi-professional Scottish soccer player and world pro 120 yards record-holder, had tried seven times beforehand to win Australia’s richest and most prestigious sprint race and, for whatever reason, had failed on each occasion.

The Stawell bookmakers loved him. His supporters loaded up their bags nearly every time he raced and they were delighted the Easter bunny was back in Australia with another plane full of Scottish loot for them.

He could run, though. In 1970, he won the 100th staging of Britain’s most famous sprint, the Powderhall Gift, and two years later defeated Mexico Olympic Games 200 metres gold medallist Tommie Smith to claim the world professional sprint championship.

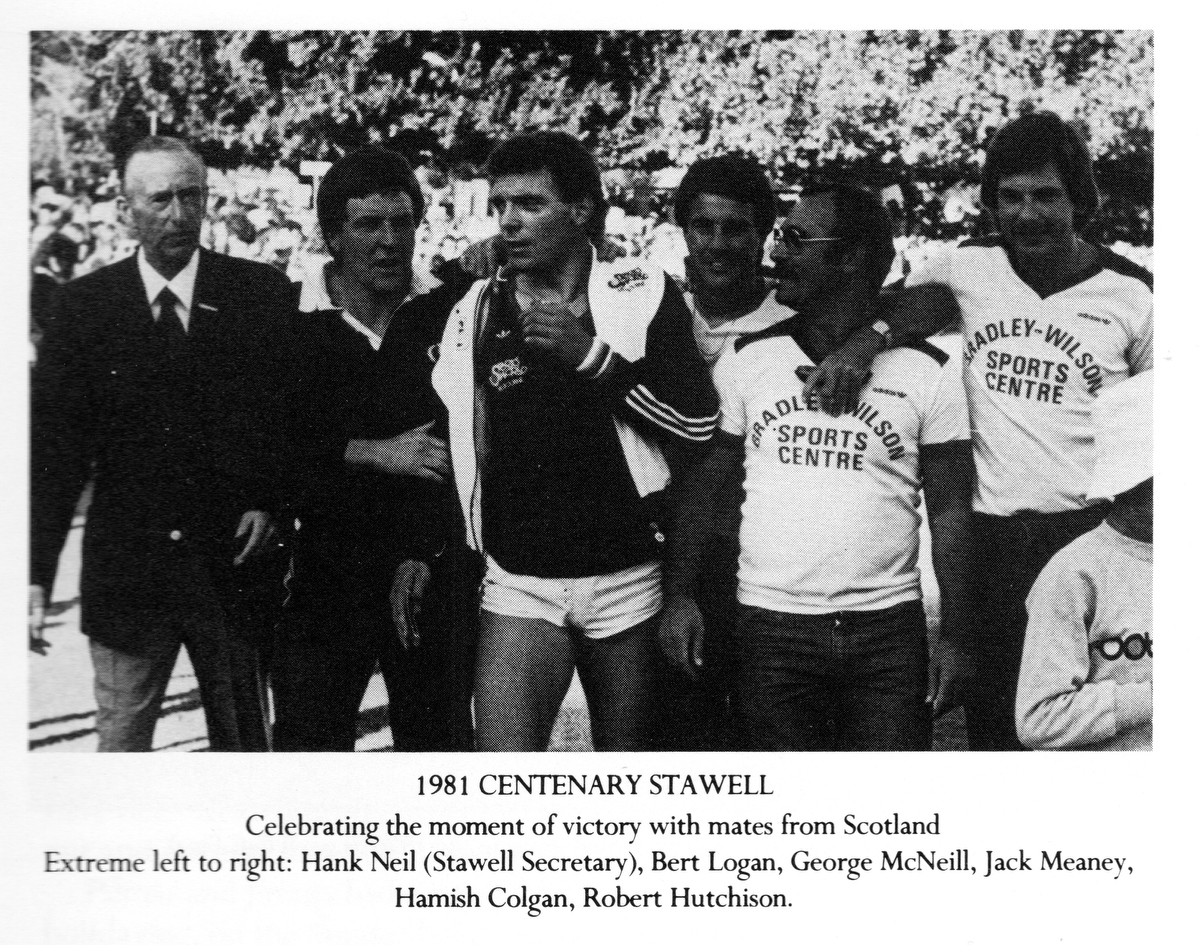

In just a few days, at the age of 34, he would line-up on Stawell’s 120-metre uphill grass track at Central Park in pursuit of a unique double – the Stawell Gift was also celebrating its 100th running and George wanted his name on that slice of pro running history.

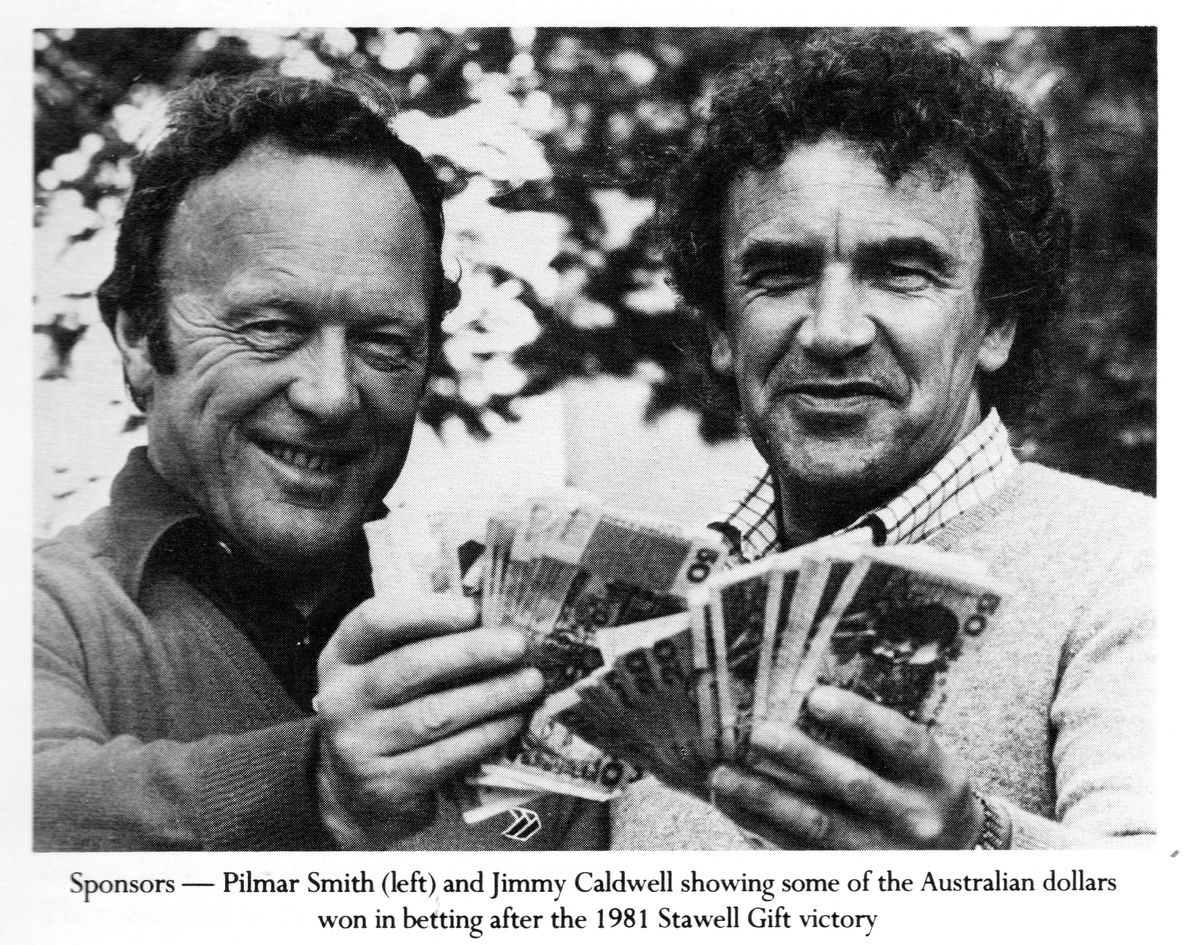

My uninvited guests in the sports room were the pint-sized, mop-haired Jimmy Caldwell, a bustling character who ran a country pub 50 kilometres from Edinburgh, and his more subdued and astute compatriot Pilmar Smith, a bookmaker who specialised on the greyhounds, but had enjoyed success in instigating plunges on pro runners in Scotland.

“Would you like a drink?” Jimmy gushed.

I looked at my watch and it was 9.45 a.m. What the heck, I thought, there seems a good story in these blokes.

The stable bar at the nearby Southern Cross Hotel opened at 10 and we were the first customers. Jimmy ordered two beers and a mineral water. As zany as he was, I discovered he was a teetotaller.

“How much are you going to have on George?” I inquired, angling for my story.

Wee Jimmy surveyed the empty bar, unzipped his fly, and withdrew the biggest wad of $50 notes I’d ever seen from inside his jockettes.

Grinning from ear-to-ear, he said: “There’s 5,000 bucks in this little stash.”

“Do yourself a favour,” I responded. “Put it back where it came from and get the first flight out of Melbourne. George can’t win.”

I had warmed to my new-found Scottish friends and did not want to see them lose a fortune. I truly believed that George, although handicapped to run from the seemingly-generous mark of four metres, was a dreamer who had succumbed to Stawell’s intense pressures far too many times for my liking.

“You’ll see,” Jimmy fired back. “This is the year of George McNeill and Scotland.”

I did see. I was covering my eighth Stawell Gift carnival for The Herald and had been privileged to witness the burly little Madagascan Jean-Louis Ravelomanantsoa become the first sprinter to win from scratch in 1975, and then the brilliant American Warren Edmonson land the prize from 1.25 metres in ’77.

But nothing matched the pure theatre which surrounded George McNeill’s quest. Jimmy hit the bookies’ ring like a tornado on the Saturday morning before the heats, but was crafty with his outlay. The eager bagmen accommodated him and remained calm. Like me, they reckoned the Scot was history.

George impressed in his heat, winning comfortably in 12.2 seconds. Wee Jimmy and Pilmar really started to get busy in the ring, reducing the load in Jimmy’s jockettes and giving the bookies a slight touch of the jitters. Their discomfort turned to abject fear on the Monday afternoon when old man George clocked fastest time of 12 seconds in the semi-finals and was installed as the raging hot favourite.

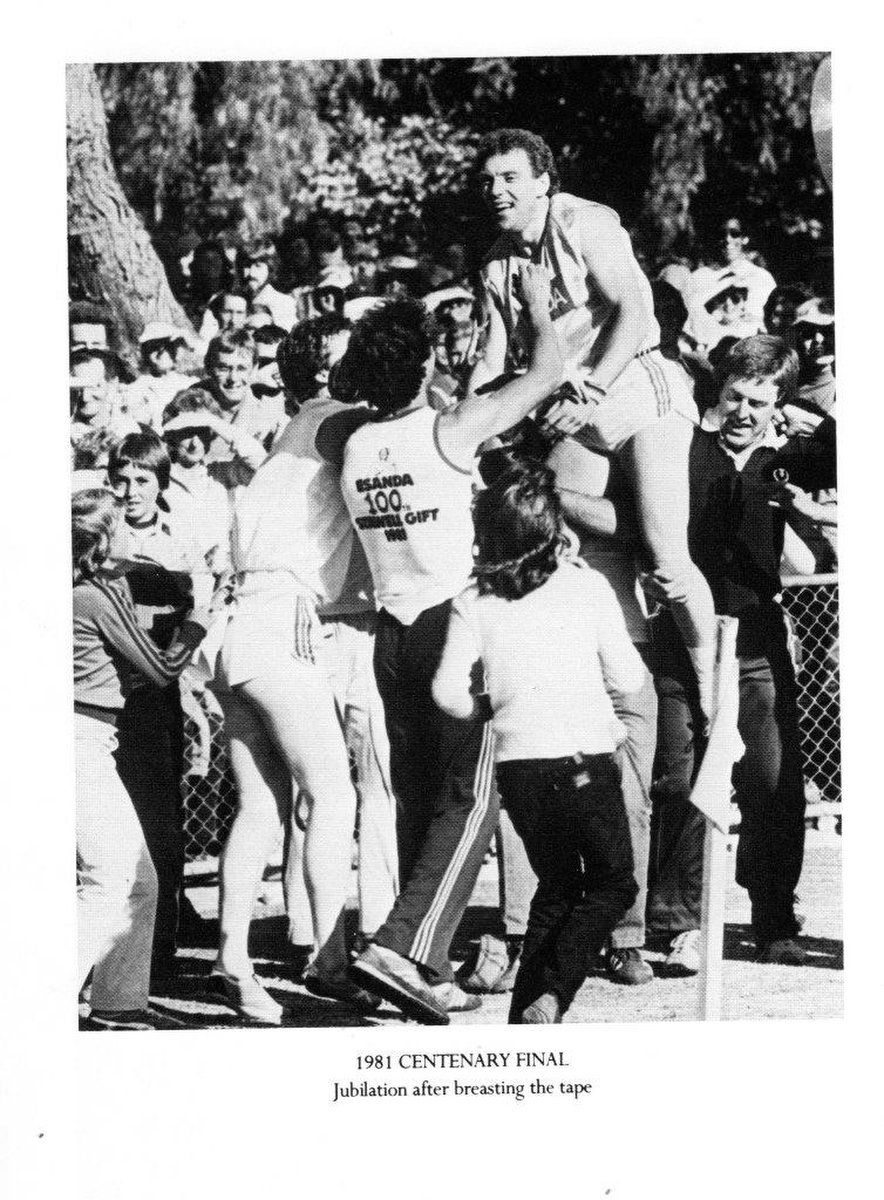

With Jimmy’s jockettes now empty and the bookies trembling, George lined up an hour later for the final against five nerve-wracked rivals. The result was never in doubt. He won in the scintillating time of 11.9 seconds and was cheered wildly by the 18,000-strong crowd as he proved that perseverance does indeed pay.

A bewildered George stood on the podium to collect his $12,000 first prize and a cartload of other trophies and goodies. Tears streamed down spectators’ faces when he sang “O Flower of Scotland”.

In the meantime, Jimmy and Pilmar were on a mission, collecting loads of money from most of the devastated dozen or so bookies in the ring. Later that evening, Jimmy invited me down to a nearby house and opened a bedroom door. To my amazement, the bed was smothered in cash of all denominations.

I had never seen so much loose cash. It was being meticulously folded into tight rolls and inserted into shoulder bags. I was told there was $40,000 on the bed.

When I returned to my motel room much later that night, there was a case of champagne on my bed. Jimmy and Pilmar were already on a plane back home to Scotland and I have not seen nor heard of them since.

George now makes a living as a raconteur and makes regular visits to Australia for speaking engagements. He is wonderfully entertaining.

I no longer drink beer at 10 o’clock in the morning.

JOHN CRAVEN was a highly-regarded sportswriter at the Geelong Advertiser, Launceston Examiner and Melbourne Herald before leaving full-time journalism in the early 1980s to embark up on a career as a publisher-promoter.

His company, Caribou Publications and Events, grew into Australia’s largest cycling promoters, employing up to 150 full and part-time staff, and organising the Herald Sun Tour for 16 years, the Melbourne to Warrnambool for 18 years, and creating other modern-day classics.

Craven has written three books – the biographies of Raelene Boyle and racecaller John Russell, and an acclaimed history of the 122-year-old Melbourne to Warrnambool Cycling Classic.

He is currently collaborating with the recently-retired race broadcaster Greg Miles on his biography.

Discussion about this post