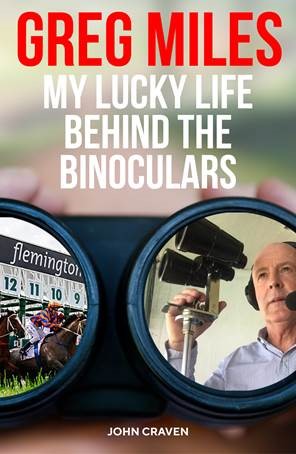

HE called a record 36 Melbourne Cups – two more than the greatly-admired Bill Collins and three ahead of his mate and mentor Joe Brown. Greg Miles was the voice of Australian horse racing for nearly four decades. Now he has told his own, colourful story, in collaboration with award-winning journalist and sports promoter John Craven. It makes for great Spring Carnival reading.

SPORTSHOUNDS brings you two exciting chapters from My Lucky Life Behind The Binoculars. You can get details of where to attend the book launch and buy the book at the foot of each chapter.

MY legs quivered and hands trembled as I commenced the challenging ascent to the cramped broadcast box at Melbourne’s compact Moonee Valley racecourse. It was Monday, January 27, 1986, and my heart rate was at record levels, upwards.

“I should have called this off,” I muttered to myself as I negotiated four levels of escalators to the top spectator-viewing deck on the course’s main grandstand. “No, it’s too late now,” I countered.

I continued my climb up a three-metre steel ladder which led me to a covered walkway on the roof. After scaling another eight steps I took up my position and clutched my binoculars in readiness to call the celebrated William Reid Stakes, a 1200-metre dash worth $100,000 prizemoney, for the Australian Broadcasting Commission.

To my far left, in pokey one-man confines, were the legendary Radio 3DB caller Bill Collins and the course broadcaster, Frank O’Brien. A bevy of judges occupied the middle section. Then, beside them, were the former 3UZ luminary John Russell and Channel 10’s Clem Dimsey. The ABC was allocated the extreme right-hand corner, not a great angle for accuracy in tight finishes. None of my colleagues knew how wretched I felt, thankfully.

About an hour earlier, I’d handed over all the cash I could muster to a gentleman named Harold Ford. It totalled $4,000 and Harold’s mission was to invest the entire bundle on the striking chestnut bush sprinter Campaign King in the Reid Stakes at the anticipated odds of up to 4/1.

Harold was a close friend of my mentor, the much-admired former ABC caller Joe Brown who was also present on-course, and it didn’t take Joe’s mate long to give me some disturbing information. He explained that Campaign King opened up as the raging 6/4 favourite with bookmakers and suggested that I may wish to gracefully withdraw.

“Just do your best,” I told him. I felt that I was probably making a mistake and that I’d been over-optimistic, but I was on a runaway train and there was no retreat. Harold did do his best and averaged 13/8. But the grand plans of my wife Alison and I to reap a monstrous haul were severely diluted. That plot was hatched only 10 or so days beforehand.

We were a blissful eight months into our marriage. We had been knocking around together for about seven years before we exchanged vows and relished the great Australian dream of owning our own home. There was a seemingly-mountainous obstacle, however.

Our adventurous honeymoon had taken us to Europe and the United Kingdom for a magnificent three months. We spent-up big-time and there wasn’t much left in the biscuit tin when we returned to Melbourne and eventually moved into a modest second floor rented flat in the Western seaside suburb of Williamstown.

An average home in historic Williamstown in the mid-1980s cost about $100,000. Our combined savings was a meagre $4,000. The gulf was enormously-deflating and we needed a fast solution to raise the $10,000 deposit, as house prices were beginning to soar.

“I’ve got an idea,” I said to Alison as we mulled over our dilemma one evening.

“Oh yes, what’s that?” she responded, casually.

“I think we should have a little wager on Campaign King in the William Reid Stakes,” I enthused. “We could get four-to-one, at least three-to-one, and if we plonk the whole four thousand on we’ll finish up with twenty grand!”

“Will it win?” she inquired, a legitimate question considering it was our entire stash.

“He’ll win, all right,” I assured her. “I am certain of it.”

“Okay,” she said, trustingly “It makes sense. Let’s do it.”

My super-confident assessment of Campaign King was forged toward the end of 1985 when I led an ABC television crew to the traditional country farming township of Berrigan in the Southern Riverina region of New South Wales. Located 257 kilometres North of Melbourne and with a population of around 900, it would be spot-on to suggest that Berrigan was then a one-horse town.

Campaign King was trained on the local track by Les Theodore, a tall angular-looking character with a reputation as a bit of a larrikin who spoke out of the side of his mouth. But he was an outstanding horseman and, upon arrival, we caught up with Les and a few of his mates, including the prominent Riverina trainer Bert Honeychurch, at the Berrigan Hotel, a convivial watering hole which served its first thirsty customers in 1888.

The Berrigan racecourse had a similarly-fascinating history. Its initial meetings in the 1890s were conducted in the Sydney-style clockwise direction, changing to the Melbourne anti-clockwise method in the early 1900s. Raising the money to stay afloat was a continual challenge for the Berrigan and District Racing Club whose members grew wheat crops and grazed cattle in the centre of the course to generate funds for prizemoney.

There was no shortage of money when Campaign King was around, however. The cheerful Berrigan townsfolk knew they had a top horse in their midst. You could feel the buzz when the chestnut’s name arose.

Campaign King, only a three-year-old, had started 17 times for nine wins, three of them on the local track, which we visited early the following morning to watch him gallop impressively.

Les gave us the good oil, virtually straight from the horse’s mouth: “He’ll win first-up in the William Reid Stakes,” he declared. That was music to my ears.

Just a few weeks’ later, as the 11-horse field of star-quality sprinters lined-up in the Moonee Valley barrier stalls, my confidence in a perfect outcome had diminished dramatically but, despite the nervousness, I kept telling myself that I must deliver a professional and unbiased call for the ABC’s nationwide listeners.

“They’re off,” I calmly announced as the wall of speedsters bounded from the gates and the Harry White-piloted baldy-faced Berrigan champ immediately dropped to the tail-end. I believe perspiration dripped from my brow as my race description descended into an obliterated blur, at least for me.

The home turn loomed towards the notoriously-short straight and Campaign King ran into trouble. I was so nervous I didn’t see the interference happen. Somebody told me about it afterwards.

The Gary Willetts-guided King Phoenix and West Mayo, urged on by Bob Durey, launched into a desperate struggle down the straight, with Campaign King nowhere within range… until, seemingly exploding from the proverbial clouds, he lunged at the straining leaders on the finishing line.

I was near-speechless. There was mumbled background talk in the commentary box of a triple dead-heat. So close was the margin that the chief judge Ken Sturt called for a three-way developed print from the photo-finish camera operator.

The tension was excruciating, but the agonising gap between the actual finish of the race and the announcement of the verdict gave me a chance to take some deep breaths and try to stop shaking. The event took only one minute 10.80 seconds to run, but it seemed like an eternity before the winning number was semaphored into the frame on the judges’ tower.

“Number eight, Campaign King has won it,” I screamed. I didn’t care how loud I yelled into my ABC microphone. My relief was indescribable. The official margins were a short half-head by a short half-head.

Harold Ford collected around $10,500 in cash and presented it to me after the final race on the card. I gave him $200 to shout his mates a few drinks at the Tullamarine Hotel. I stuffed the rest into my suit-coat and trouser pockets, and they bulged. Then I drove home to Williamstown.

“How’d you go?” Alison asked matter-of-factly as I walked in the front door. She had listened to my radio call.

I didn’t need to say anything, but began extracting money from my pockets and throwing it on the kitchen table. There was a $10,000 mountain of it, including our $4,000 outlay, certainly enough for our house deposit.

Campaign King soon after was acquired by the Bart Cummings stable and ended his fabulous 56-start career with 23 wins, five seconds and two thirds, for a whopping $1,832,840 in prizemoney.

Alison and I paid $80,000 for our little weatherboard two-bedroom home in Charles Street, Williamstown, and took up residence in October, 1986.

It’s little wonder that I have a super-elevated assessment of Campaign King’s status in Australian racing folklore.

GREG MILES: MY LUCKY LIFE BEHIND THE BINOCULARS will be launched at Melbourne’s Mail Exchange Hotel, 688 Bourke St., on Tuesday, October 16.

Books will be on sale at the Mail Exchange from 1.30-2.30 p.m.

Members of the public will be able to meet Greg and have their books personally signed.

GREG MILES: MY LUCKY LIFE BEHIND THE BINOCULARS.

By Greg Miles and John Craven.

RRP: $39.99.

Wilkinson Publishing,

Level 4, 2 Collins St.,

Melbourne. Vic. 3000.

P: 03-96545446.

www.wilkinsonpublishing.com.au

JOHN CRAVEN was a highly-regarded sportswriter at the Geelong Advertiser, Launceston Examiner and Melbourne Herald before leaving full-time journalism in the early 1980s to embark up on a career as a publisher-promoter.

His company, Caribou Publications and Events, grew into Australia’s largest cycling promoters, employing up to 150 full and part-time staff, and organising the Herald Sun Tour for 16 years, the Melbourne to Warrnambool for 18 years, and creating other modern-day classics.

Craven has written three books – the biographies of Raelene Boyle and racecaller John Russell, and an acclaimed history of the 122-year-old Melbourne to Warrnambool Cycling Classic.

He is currently collaborating with the recently-retired race broadcaster Greg Miles on his biography.

Discussion about this post