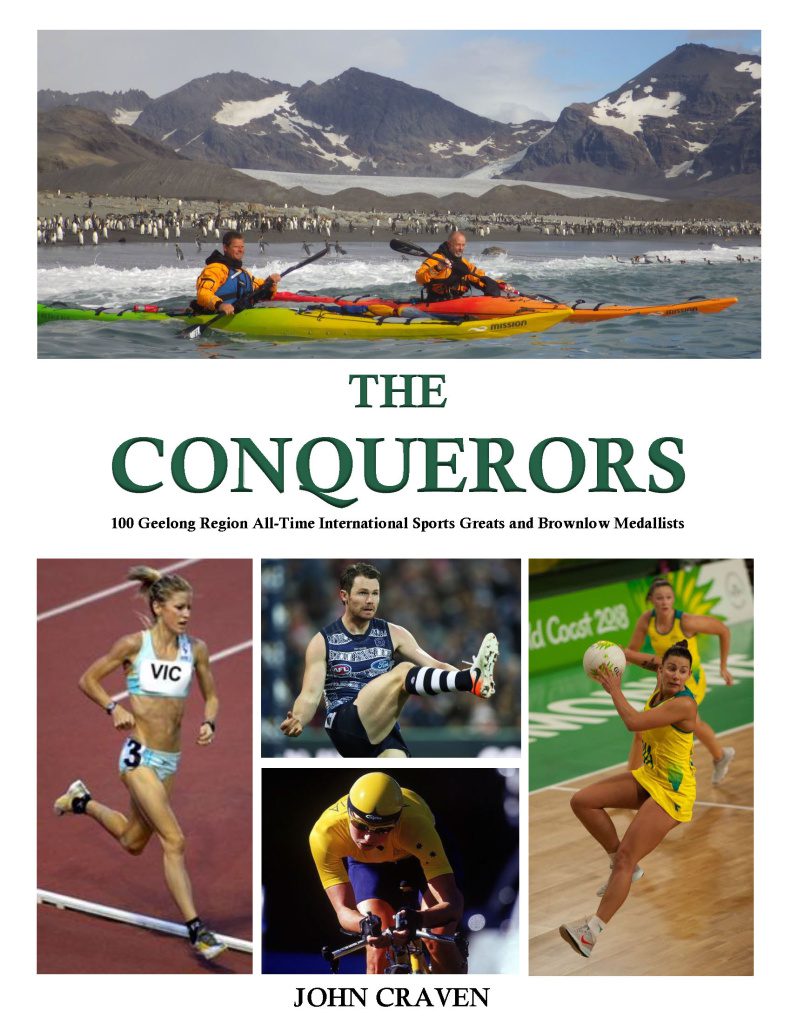

In his new book “The Conquerors” author John Craven compiles Geelong’s top 100 sports stars and has shared a chapter with Sportshounds readers:

June Ford tells a delightful tale about her mother, Alma Catherine Condie, otherwise known as Mrs. Carji Greeves, wife of the Victorian Football League’s 1924 inaugural Brownlow medallist who blazed the trail for Aussie Rules football in the United States.

Carji and Alma were married in 1934 at St. David’s Presbyterian Manse in the inner Geelong suburb of Newtown, just a drop punt from The Geelong College where the youthful Greeves had excelled in football, cricket, rowing, tennis and almost any sport he tackled.

The astute Alma was well aware of the precious significance of the Brownlow Medal – the Victorian Football League’s highest annual individual award for its fairest and best player, and also its value. It was struck in 18-carat gold.

Wherever she lived for the next 70 or so years, she popped the medal into her handbag whenever she left the house – whether it be a brief shopping trip or an extended holiday.

Carji had given her permission to have the medal made into a brooch and she’d pin it to the inside of her bag – in amongst her lipstick, make-up, keys, note books and all sorts of women’s paraphernalia. She just didn’t trust anybody with it or run the risk of theft.

“Mum pranged her old car when she was 92 and it was a write-off,” June confides. “She was housebound and unhappy, and literally demanded her independence.

“So I took her to a used car place in West Fyans Street, Geelong, and a display of Geelong Cats memorabilia was on the wall. Dad’s picture was up there and the salesman was explaining to us that he was the first Brownlow medallist.

“’I’ve got the medal,’ Mum glowed, as she dug into her handbag.

“The sales fellow was blown away and could hardly believe it. She wasn’t flashing it around, she just loved sharing it with people who were interested. Mum finished up with a blue Ford Laser!”

There are a multitude of captivating aspects to the legend of Carji Greeves, starting in September, 1839, when his great grandfather Dr. George Paul Adolphus Greeves and his twin brother Augustus set sail from England to Australia aboard the 460-tonne barque Lord Goderich, with 51 passengers aboard. Thirteen rough-weather days later, the Lord Goderich collided with the Sydney-bound Sophia off the Isle of Wight. Chaotic scenes prevailed.

The wounded Lord Goderich somehow limped to calm waters, minus bowsprit and cutwater, and with other serious damage. A female passenger later wrote that she was safe in Portsmouth and was “most reverently thankful for our merciful deliverance. The sound of wind and rain was most awful, and the waves were mountains high. We several times feared the roof of our cabin was breaking in. For a short time both the captain and mate thought we should go down.”

The repaired Lord Goderich eventually arrived in Australia on May 25, 1840, docking in Tasmania. Dr. George Greeves, his wife Ann, three children and brother Augustus, had survived a harrowing ordeal. The youngest child – christened Edward Goderich Greeves – was born during the tempestuous nine-month voyage.

Carji was the third Edward Goderich Greeves. His ship-bred grandfather died in Ballina, New South Wales, in 1905, but had made his mark in Australia. He married Julie Anderson, once courted by Tom Wills, the founder of Aussie Rules football, and they farmed at Borriyalloak, Skipton, in Victoria’s Western District. They had seven children. The youngest was the second E.G. Greeves, born in 1878. He was known as Ted.

The strong-willed Ted attended Geelong College and was an outstanding footballer. He captained the school team and played 20 games for Geelong as a centreman from 1897-99. He married Frances Nasmith in January, 1903, and the newly-weds took up residence on Garstang, a farming property in the rural Gippsland town of Warragul. The third E.G. Greeves was born on November 1, 1903.

Upon the birth of their son, Ted and Frances proudly showed him off to the prominent New South Wales golfer, the Honorable Michael Scott, a family friend who was visiting the Greeves’ after returning from Melbourne where he attended the popular stage play, the Rajah of Bong. Its lead star was named Carjillo (little prince).

Scott peered into the bassinette and observed that the baby possessed olive skin: “Hello, Little Carji,” he said. That marked the abandonment of the Edward Goderich christian names. It was Carji for the rest of his life.

Ted and Frances Greeves were farming nomads. Carji was only three when his parents vacated Warragul and relocated to a property alongside the Richmond River at Lismore, NSW. Four years later, they moved to another Lismore, this time in Victoria, not far from Skipton.

Carji attended the tiny one-teacher Struan Dam State School at Rokewood. Incredibly, two grades below him was a raw-boned lad who went on to become arguably the most revered, feared, awe-inspiring, durable and successful personality in Geelong Football Club history – Reginald Joseph Hickey.

Born on March 26, 1906, of Irish descent, Reg Hickey appeared in 245 games over 15 years for Geelong as a rugged, speedy, clear-thinking defender. He won two best and fairest awards, played in the 1931 premiership side, was captain-coach of the 1937 flag-winning line-up, and coach of the legendary 1951-52 premiership teams.

Hickey captained the club for nine years, finished third in the 1931 Brownlow Medal count and second in ’36, represented Victoria 18 times, and was coach in 304 games, including 91 as captain-coach.

He was chosen as captain, coach and centre half-back in Geelong’s Team of the 20th Century, was named on the interchange bench in the VFL-AFL’s Team of the Century, and was inducted into the AFL’s Hall of Fame in 1996.

In all, Hickey was officially connected with the Cats for 34 years, from 1926-59, aside from an extended stretch in the 1940s when World War 11 intervened, after he had earlier backed away from the club because of an alleged dispute with the match committee over selection procedures. He died in December, 1973.

Carji Greeves, two-and-half years older than Hickey, gave notice that he was a budding VFL champion during his formative years when he played for Berrybank. In a match against Mingay, a Mrs. Mildred Howley later penned in her recollections of life in the area that a youth in a green sweater was “rushing about,” helping inflict a terrible hiding on her team.

“I felt like kicking him – the future Carji Greeves,” she confessed.

Carji was only 12 in 1916 when he emulated his father and became a Geelong College boarder. His influence grew as the Summers and Winters rolled by. Not much is known about his scholastic achievements, but in the field of all-round sporting endeavour, he was a stand-out – a prodigy.

During his seven years at Geelong’s nationally-renowned private school he was, from 1920-23, a dashing left-hand batsman and steady bowler in the First X1 cricket team, rising to captaincy. He was a member of the First 18 football squad for three years and won the college’s senior singles tennis championship in 1922. In 1923, he stroked the Head of the River rowing crew. His leadership qualities were formally recognised when he was appointed a prefect in 1922-23.

The Geelong Football Club could barely wait to get the country teenager into a blue and white jersey, but Geelong College’s principal stepped-in early in 1923 and deflected the overtures, insisting that Carji compete for his school in the Head of the River – the blue riband Victorian private schoolboy eights championship, which drew a massive festive-style crowd to Melbourne’s Yarra River. Embarking upon a spectacular pathway of joyfully chasing awkward leather balls around dressed-up paddocks, cheered on by adoring crowds, was delayed until his rowing duties were completed.

Nineteen-year-old Carji Greeves played his first game for Geelong in Round 8 of 1923, wearing No. 20. He insisted that his amateur status be retained, and he shunned traditional football boots, preferring to wear a soft handmade kangaroo-hide variety, with stops nailed-in. He was not a big specimen, standing 175cms and weighing 76kgs. He kicked proficiently with both feet – his disposal was, in fact, brilliant. He was not a speedster, but he knew instinctively how to get the ball.

Founded in 1859, the Geelong Football Club, known as the Pivitonians, played its first official match against Melbourne on September 1, 1860, at the Argyle ground in Aberdeen Street. Geelong fielded 25 players, Melbourne 20. The no-holds-barred match was drawn. Geelong was a foundation member of the Victorian Football Association in 1877 and won seven premierships before, 20 years later, leading a breakaway group from the VFA with five other clubs and two invitees to form the Victorian Football League.

Geelong was success-starved for nearly three decades in the new VFL. After a dismal 1922, the Geelong Advertiser commented: “Unquestionably the season’s failure can in many respects be attributed to lack of determination, incomplete training methods, and an imperfect education in the finer points of the game. Another fatal and distressing feature which has been eating cancer-like into the very vitals of the organisation, has been a regrettable absence of unanimity in the government affairs of the club.”

So desperate was Geelong after a patchy string of early losses in 1923 that the captain Bert Rankin, aided by star centre half-forward Lloyd Hagger, adopted a suggestion by Melbourne Herald newspaper cartoonist Sam Wells that a black cat mascot needed to be introduced into the club, hopefully to execute a change of luck. The Pivitonians nickname was subsequently phased out in favour of a fresh moniker – the Cats.

Whether it was the cat-inspired influence or the arrival of Carji Greeves, the club’s fortunes swung dramatically skywards after the Western District farm lad and Geelong College scholar commenced his illustrious 10-year association with the Cats, starting out as a rover and half-forward before being switched into the centre. The positive results were almost instantaneous, with Geelong reaching the finals in 1923, only to be beaten by Fitzroy in the first semi.

While on-field prosperity largely eluded the Cats, the Geelong Football Club was a persuasive and powerful driver in the organisation and progress of the VFL in its developing years. The shining star in the administrative zone was Charles Brownlow, the intelligent and measured son of English parents who migrated to Australia in 1858.

Born at Cullin Lane, Geelong, on July 25, 1861, Charles Brownlow showed keen interest in Aussie Rules football as a schoolboy and later on when assistant librarian at the Yarra Street Methodist Sunday School. His parents, Charles and Eliza, were sternly opposed to having their son play such a barbaric sport, but by 1879 he was lining-up regularly for North Geelong under the name of Charles Green, in defiance of his mother and father.

The young Brownlow may have tried to shield his real name in fear of his parents’ wrath, but that was a battle he was doomed to lose. His football ability was so visible that he was recruited by the Cats in 1880. So began more than 40 years of constructive dedication to the Geelong Football Club, the VFA and the Victorian Football League – and eventually an elevated place in footy history.

Brownlow, who at various stages of his adult life worked as a watchmaker, jeweller and tobacconist, and was an outstanding oarsman with the Corio Bay Rowing Club, played for the Pivitonians as a solid defender from 1880-84, and in 1887. He was elected captain in 1883 and was a member of the ’83 and ’84 premiership teams. He was appointed secretary in 1885 for a small remuneration, and held the position until the early 1920s. In between, he coached the club in 1886, ironically the year that marking the ball with both feet off the ground was tried.

As Geelong’s delegate to the VFA, in 1891 he argued successfully that players should take up their allotted positions on the field before matches started, and that the central umpire should bounce the ball in the middle of the ground as a signal to commence the game, and again after each goal was scored.

Upon its foundation, Brownlow was appointed Geelong’s delegate to the VFL and for the next 21 years was deeply involved in the discussion and implementation of a litany of innovations, including the introduction of boundary umpires in 1904, the numbering of players (1911), the appointment of stewards (1912), the creation of the Football Record (1912), the establishment of the Independent Tribunal (1913), and the setting up of the VFA-VFL clearances agreement (1913).

The civic-minded Brownlow was the VFL’s vice-president from 1911-16 and chairman of the permit and umpires’ committee from 1911-22. He was a delegate to the newly-formed Australasian Football Council, later becoming chairman. Not surprisingly, Geelong named a new grandstand at its Corio Oval headquarters after he and another club legend Henry “Tracker” Young.

Charles Brownlow died relatively young, on January 23, 1924. The father-of-five lost a two-year battle against chronic nephritis, eventually succumbing to a cerebral haemorrhage. Such was his popularity that his funeral procession to Eastern Cemetery was a half-mile long. Four carloads of VFL and AFC representatives travelled from Melbourne to Geelong for his farewell.

It was fitting, therefore, that when the VFL shortly afterwards created an annual award for its fairest and best player, it was named the Charles Brownlow Medal, in his esteemed honour. The rules were simple – a single vote to be awarded by the central umpire to the fairest and best player in each match, the one with the most number of votes at the conclusion of the home and away season to be crowned the Brownlow medallist.

In just his second season in the blue and white hoops, the dynamic Carji Greeves polled seven votes to win the 1924 Brownlow Medal. At the tender, but not-so-delicate age of 20 years 321 days, he triumphed narrowly from Melbourne’s Bert Chadwick and Essendon’s George Shorten who tied for second with six votes. The Little Prince had cemented the Greeves name into the annals of Australian sport with his gigantic achievement.

Nearly 100 years on, how life has changed! Despite its status as the inaugural Brownlow Medal count, votes were tallied-up at the VFL’s Melbourne headquarters on September 17 and the results were announced without fanfare or any glittering dinner at a majestic city hotel ballroom.

“Carji never received the medal until months later,” June Ford relates. “He was at training at Corio Oval one night during the 1925 season when an official walked on to the ground and gave it to him. Carji put it in his pocket and got on with training.”

Carji’s crowd-pleasing style of football, with his penetrating kicking, superb marking skills and fair-minded conduct, had a magnetic impact on central umpires. He finished runner-up in the Brownlow three times over the next four years – in 1925 to St. Kilda’s Colin Watson, in 1926 to Melbourne’s Ivor Warne-Smith, and again to Warne Smith in 1928. He was fourth in 1927.

He may not have snared the Brownlow, but success in a joyous, different form greeted Carji and his team-mates in 1925. The Cats won their first VFL premiership after a 29-year barren slog and they did it in grand fashion, defeating Collingwood by 10 points before a record 64, 288 spectators at the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

It was a stellar season for the Cats who won 15 of their 17 home and away matches, including a dozen on end, and topped the ladder in the 12-team competition. Captain-coach Cliff Rankin kicked five match-winning goals in the Grand Final.

Thousands of jubilant fans turned up to Corio Oval to welcome and cheer the players the day after premiership glory. The Geelong Advertiser reported: “After congratulatory speeches on both sides, supporters of the club, headed by those popular players Stan Thomas and Arthur Coghlan, set about to bury the ‘Magpie.’ The Collingwood visitors appreciably assisted in the ‘solemn’ service as they acted as mourners, and stood bare-headed during the ceremony.”

With a Brownlow Medal and premiership under his belt, plus consistent – sometimes dazzling – performances over six seasons which earned him matinee idol adoration from Cats fans, Carji was widely recognised as one of Aussie rules football’s most distinguished players. It was this greatly-deserved reputation which led to a fascinating assignment on the international stage.

The University of Southern California fielded a gridiron team in America’s wildly- popular collegiate competition, but in the 1927-28 Winter season managed to score a paltry one field goal because of what was deemed as poor kicking. The uni’s treasurer Andrew Chaffey, familiar with Australia through his family’s involvement in the foundation of Mildura and Renmark, convinced USC management that an Aussie rules footballer was needed to instruct players in the fine art of kicking the ball.

Chaffey and his brother Ben communicated with the leading sportswriter J. A. Alexander, of Melbourne’s Sun-News Pictorial, asking that he seek out a player of fine character who was “a great kick, an all-round sports person and a good communicator.” After a prolonged search, the journalist recommended Geelong’s E.G. “Carji” Greeves.

J.A. Alexander took great pride and licence in breaking the story on Carji’s appointment, a situation that provoked a hostile reaction from some quarters of the Geelong Football Club, especially its president J.A. Thear.

Alexander wrote in The Sun: “I chose ‘Carji’ Greeves as being the type of man best suited to the needs of the University. He is a Brownlow medallist, a magnificent all-round athlete and, in every respect, a splendid type of Australian manhood.”

Cats supporter W.J. Tarr was compelled to pen a letter to the editor of the Geelong Advertiser: “I see in Tuesday’s issue of your paper that the Geelong Football Club seems annoyed to think that Carji Greeves went ahead with arrangements without informing the club of his intentions.

“Now, sir, it appears to me that the reason for his secrecy sticks out a mile. Carji was chosen by the sporting writer of a metropolitan daily and it would have been eminently good business on their part to insist that they should be the first to publicly break the news.

“As for the suggestion that the Geelong Club made Carji the footballer he is, that is all bunk. He was a furnished footballer before he came to the club; and experience, not coaching, has made him perfect. The opinion of 99 per cent of club members is that Carji has made the club, and not the club him.”

On Saturday, August 4, 1928, a bon voyage “Grand Concert & Presentation” was organised by Mr. W. Gallagher to honour Carji Greeves at a packed-out Geelong Mechanics Hall. The musical and recital program featured 16 acts, including solo and duet performances from Miss Eileen Pascoe Webb and Misses Searle and Trounce, and stirring renditions from the locally-renowned St. Augustine’s Band. Carji sailed from Sydney for America on the Maunganui five days’ later.

Even the Collingwood Football Club was excited by Carji’s USA breakthrough. The Magpies’ assistant secretary R.T. Rush wrote him a letter on July 18: “By direction of my committee, I have the honour to convey the hearty congratulations of the Collingwood Club on the American appointment you have received,” he penned.

“In our opinion the selection has been wisely made, and apart from your athletic ability, we feel confident you will prove a worthy representative of young Australia in the acid test to which you will no doubt be subjected by our Yankee cousins.

“We hope the result of your visit may be the introduction of our great game across the Pacific, and trust you will still favour the football fans with an occasional word of your progress in the land of the Stars and Stripes.

“With every good wish from our players and Committee for your success.”

The University of Southern California in Los Angeles had about 12,000 students, many of whom were on sports scholarships. The “Trojans” made tens of thousands of dollars when they won a game. Carji was widely feted in the USA, but his assignment was not without challenges. He quickly identified that players drop-kicked off their toes instead of their insteps, thereby getting height but not distance, and it was on correcting this weakness that he concentrated.

In a letter to his parents, Carji expressed his frustrations. He said the students would watch him kick, then walk away, explaining that they simply could not do it. On repeating the exercise, they would again shun the instruction and start throwing the ball to each other. He described their attitude as “really heartbreaking.”

Displaying true Aussie fortitude, he persevered and managed to persuade a couple of players to try his method. Soon they were kicking the ball 50 to 60 yards, a far cry from the 20 to 30 yards they once regarded as an acceptable performance. The results were stellar. The Trojans won the 1928-29 Championship of America title, scoring 21 field goals for the season. Carji was invited to give an exhibition of his kicking at a stadium holding 90,000 spectators and was asked to stay in the USA. He declined, departing for Australia by ship in January, 1929.

Upon his return to the Geelong-Western District region, Carji proudly announced to his Cressy-based father that he had been offered the Australian franchise for a stunning American invention – neon-lit signage, and was keen to accept.

“Who on earth would want flashing lights in front of their buildings,” Ted Greeves responded. “You won’t have time, you have a farm to run.”

Carji continued to be a dominant force with the Cats, despite incurring a severe knee injury in 1930 which continued to hinder the tail-end of his football career. He played in Geelong’s 1931 premiership side and retired after the Round 7 match against South Melbourne at Corio Oval in 1933, having amassed 124 games and 17 goals. He represented Victoria seven times in interstate encounters.

Upon his departure from Geelong, he was captain-coach of Inglewood in the Korong Valley League and coached Wimmera League clubs Warracknabeal and Ararat. A knee cartilage operation terminated his life as a footballer, and during the 1930s he contracted pulmonary tuberculosis and emphysema. Carji and his wife eventually settled in Ararat where they had two daughters, Dawn and June. He worked as the local manager of Motorspares.

While his football escapades were in full bloom, Carji was not lost to cricket. He played for Melbourne in 1924 and for the Victorian Colts against South Australia in ’25. The next year, he represented Geelong at the fiercely-contested Country Week competition, securing the best aggregate tally, highest individual score, and the batting average.

Additionally, he rowed with the Barwon crew in the Henley-on-the-Yarra, and the Victorian Rowing Association’s senior eights. In tennis, he won the Northern Districts singles championship at Bendigo in 1928. Perhaps his grumpy father was correct – combined with his duties on the family farm at Cressy, Carji didn’t have time to be pedalling neon lights.

June Ford also attests to the fact that he was an outstanding marksman: “While teaching me how to drive on the back roads of Ararat, he’d take me hunting for rabbits and quail. He was a great shot,” she smiles. June attended Ararat High School and was nicknamed “Carj.” She didn’t like it much.

June, with her daughter Cate and son Andrew, moved to the seaside township of Anglesea in 1974. Her mother soon followed. June worked successfully in public relations in Geelong and, after her mum’s death in 2004, she developed an uneasiness about the responsibility of being the custodian of her father’s precious Brownlow Medal. She sold it in 2007.

The medal has changed hands several times since and is now owned by the Geelong Football Club after a small consortium of Cats benefactors and supporters purchased it in 2019 for $250,000: “The medal is on display in the Cats’ museum and this treasure is now where it belongs,” says the club’s effusive historian and former committeeman and vice-president Bob Gartland.

Carji may have won the inaugural Brownlow Medal without fuss or frenzy, but his no-frills accomplishment is now, thankfully, recognised and revered wherever the Australian rules code is played. The Geelong Football Club’s annual fairest and best award is named the Carji Greeves Medal. In 2002, an exclusive Melbourne-based Carji Club was founded. It operates as a fund-raising charity group through its unique, high-profile lunches. In 2011, he was inducted into the Old Geelong Collegians’ Notables Gallery, and an imposing monument was erected in memory of Carji and Reg Hickey on the site of the old Struan Dam State School in Lower Darlington Road. Carji is also featured in artist Harold Freedman’s mural of the Western District in the State Public Offices.

Carji Greeves died of a heart attack in Ararat on April 15, 1963, aged 59. He was inducted into the Australian Football Hall of Fame in 1996 and the Geelong Football Club’s Hall of Fame in 2002. He was selected as the centreman in the Cats’ Team of the 20th Century, and also in the Inglewood club’s all-time great line-up.

Fame followed E.G. “Carji” Greeves wherever he tracked. Like the handsome, genuine symbol of Australian manhood that he was, his feet stayed on the ground – always.

To purchase a copy of The Conquerors, head to http://www.caribou.net.au

JOHN CRAVEN was a highly-regarded sportswriter at the Geelong Advertiser, Launceston Examiner and Melbourne Herald before leaving full-time journalism in the early 1980s to embark up on a career as a publisher-promoter.

His company, Caribou Publications and Events, grew into Australia’s largest cycling promoters, employing up to 150 full and part-time staff, and organising the Herald Sun Tour for 16 years, the Melbourne to Warrnambool for 18 years, and creating other modern-day classics.

Craven has written three books – the biographies of Raelene Boyle and racecaller John Russell, and an acclaimed history of the 122-year-old Melbourne to Warrnambool Cycling Classic.

He is currently collaborating with the recently-retired race broadcaster Greg Miles on his biography.

Discussion about this post