SEVEN DAYS IN SPORT: THERE was a lot to learn for the players and the coach alike when the cricket academy started, writes RON REED:

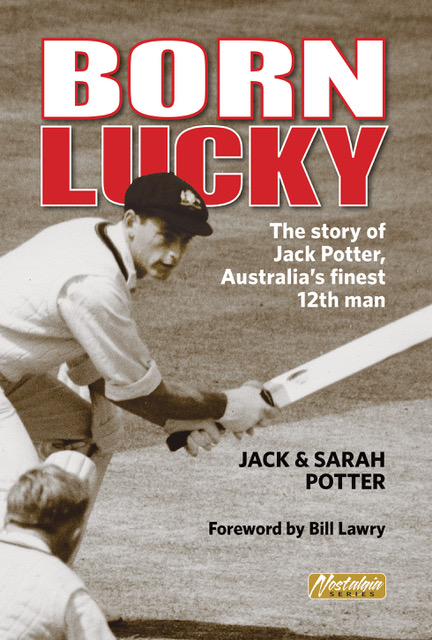

JACK Potter enjoyed two pretty good cricket careers – one as a player and one as a coach, both of which were celebrated in Melbourne on Friday when his biography, Born Lucky, was launched at a lunch put on by the Australian Cricket Society and the Victorian Taverners.

Potter, 82 – who joined in by Zoom from his home in New Zealand — is a former Victorian captain who averaged 41.22 in 104 first-class matches and got as close to Test cricket as possible without actually ever playing it. He was on the 1964 Ashes tour and was 12th man twice there and once in Australia.

But perhaps his biggest contribution to the national cause was his stint as the inaugural coach of the Australian Cricket Academy when it was established in Adelaide by Cricket Australia and the Australian Institute of Sport in 1987.

Potter is rightly proud of his three-year stint there, which saw 30 of 46 boys go on to play first class cricket, and 11 make it all the way to Test and international one-day ranks for either Australia or England, none more successfully than Shane Warne – who he taught to bowl the flipper — and Justin Langer.

But only now has he put it on record just how difficult and frustrating the job was given the scepticism and lack of support the project attracted from the cricket establishment and certain key people in it, notably, he says, the late David Hookes and the then chief executive of the Australian Cricket Board, Graham Halbish.

I don’t recall these issues being big news at the time, or being in the public arena at all, really, but they certainly would be if it was happening now.

Potter says that before taking up the job he had “a prophetic conversation” with prominent Melbourne cricket identity Bill Jacobs who warned him not to trust some of “those clowns” at the ACB.

“In those formative months we met with much resistance, cricket being such a conservative game,” Potter writes. “Many of the first-class players at the time scoffed at the ideas and methods; some on the ACB openly disagreed with the changes we were making.”

A physical education professional while he was playing, Potter was more fixated on fitness than most cricketers of his era and beyond. “It wasn’t uncommon for first-class cricketers in the 1980s to think that a beer with pie, sauce and chips during a game was a good way to relax,” he says.

He also found that “intense and entrenched interstate rivalry” created a lack of co-operation at a higher level, which contributed to Australia’s declining international performance at the time., which was the reason the academy was put in place.

While the South Australian Cricket Association was supportive, it put forward only three boys in the first year and Hookes, the State captain and its best player, made his disdain clear.

He even went so far as to refer to the AIS as ‘assholes in sandshoes’ and advised some outstanding young players, including future Test batsman and national coach Darren Lehmann, not to attend, Potter says.

Consequently, it took Lehmann a long time to realise his potential and break into Test cricket.

Budget issues threatened to send the academy out of business until the Commonwealth Bank stepped in with sponsorship, while Potter also felt that bureaucratic interference was becoming a major problem and that his role and efforts were not appreciated or respected.

Halbish, he says, “had to be consulted every step of the way even though he had little background in playing or coaching cricket. He had great difficulty handing over management and used to call every week with instructions and came to Adelaide once a fortnight to give advice.”

Potter says “my initial conversation with Bill Jacobs was always in the back of mind, now more than ever.”

In a chapter headed “The Last Straw,” Potter says the Academy was invited to send a team to tour the West Indies. He would be the coach. Except that he soon got phone calls from Greg Chappell, Doug Walters and Dean Jones, who all told him Halbish had rung them and asked them to coach the team.

After a testy conversation with the CEO, Potter felt he was becoming the victim of a personal attack. “I hadn’t taken kindly to what I considered to be Halbish’s attempts to interfere in the running of the academy and had told him so.”

The end was nigh.

He and his assistant, Peter Spence, had both become frustrated with the lack of support and the onerous workload, Spence leaving to join the Victorian Institute of Sport.

“In the end I could no longer tolerate the excuses and meddling and after nearly three years of backbreaking work, I was exhausted,” Potter writes.

“My phone call to Halbish was short and sharp: ‘You can stick your f***ing job up your f***ing arse.’”

“You wouldn’t dare resign.”

“Oh, wouldn’t I?”

“And I did.”

In the end I refused to work with a man I couldn’t trust.”

The Academy continued to churn out superstar players under other coaches, notably Rod Marsh – including Rick Ponting, Adam Gilchrist, the Hussey brothers, Brad Haddin, Mitch Johnson, Brett Lee, Glenn McGrath, Shane Watson and others – and eventually moved to Brisbane in 2004, renamed the Centre of Excellence.

Born Lucky is published in limited edition of 500 by cricketbooks.com.au.

AFTER thrashing England’s cricketers in three and a half days in the second Test India have now repeated the dose in not quite two days, both on pitches heavily favouring spin bowlers – and the usual question has gone straight to the top of the agenda. Is this good for cricket?

No, it’s not.

“Home” pitches are an acceptable part of the game and always have been, but only up to a point. There is – or should be — a limit, and when you start having two-day games you’ve just about reached it.

I must admit this is not an entirely straightforward debate.

In this space a week ago, I was happy to give a tick to the previous game, as “adding welcome variety to the dynamics of the game.” But I added: “You wouldn’t want a track like that everywhere you looked, of course, but an occasional wildcard adds an x-factor not often found these days in Australia, where the curators mostly serve up much the same everywhere.”

And that’s the thing – in all aspects of cricket, a sense of balance is essential. By serving up these surfaces at every opportunity, India has tipped the balance too far one way.

When the pace bowlers on both sides don’t even get a bowl – on day two – that is a disappointing distortion of Test cricket. Nobody wants to see four or more players reduced to spectators, or wickets falling every dozen runs or so, or a five-day match over in little more than five sessions.

Test cricket is under enough pressure without making it unrecognisable to its fans.

India, and every other country that plays the game, are entitled to tweak conditions to suit their own strengths – and there is no doubt they have thoroughly outplayed the Poms while dealing with the exact same conditions. As we discovered in Australia, they are an extremely formidable cricket team.

But this dominance should not come at the expense of the integrity of the contest. Against this latest backdrop they do need to rethink their responsibilities to the bigger picture.

JOHN Coates has his critics from time to time, but the long-serving Australian Olympic chief is entitled to take a big bow now that Brisbane is all but confirmed as the host of the 2032 Games. His presidency of the AOC will have brought the Olympics to Australia twice, an amazing feat surely unprecedented by any other individual administrator anywhere. Years ago Coates was the hands-on driver of an earlier Brisbane bid, preceding Sydney, which was never really viable, so this will be all the more satisfying in a small way.

The Queenslanders will do this well, having been in training for a long while, successfully hosting two Commonwealth Games in Brisbane in 1982 and the Gold Coast in 2018, both of which I had the pleasure of attending.

Embed from Getty ImagesForty years ago, Brisbane was a glorified country town, and indeed the event was unofficially promoted as the “gumtree Games.” It finished on a Saturday night, and one of my enduring memories is of trying to organise a wind-up dinner the next night for the small team I had been working with, only to find that almost every restaurant in town was closed because it was Sunday, despite there still being thousands of visitors walking around, similarly hungry and thirsty. The only exception we could find was a Chinese joint, because they never close in my experience.

I doubt there will be any such problem 11 years from now – I hope I’m still around to find out.

If not, the Olympics and I may have seen the last of each other, after nine previous engagements. Arrangements have been in place for some time for Tokyo to be the 10th come July, but the countless Covid precautions that the organisers are putting in place are making it an unattractive proposition. For instance, media visitors cannot go to restaurants, bars or shops or use public transport, and there are no guarantees about being able to access seats at venues to see events live, as distinct from watching on TV in work centres. Which, of course, we can do from home in far greater comfort – and almost certainly will, sadly.

NOVAK Djokovic has come and gone with yet another Australian Open tennis championship – his ninth – to support his ambition of becoming the most successful player ever, which he seems certain to achieve within the next year or two. And yet he seems to still struggle for popularity wherever he goes, Melbourne no exception. Not sure why that is, but I reckon it might be a case of giving a dog a bad name. He used to be a bit of a smart-arse in his early years and now every time he puts a foot out of line in word or deed there’s a pile-on, often without much real reason. OK, he hasn’t got the charm or charisma of Federer or Nadal, but not many have – and he’s at least their equal as a performer, no less impressive to watch. As usual, he played near-perfect tennis, even with a genuine abdominal injury, to not just win this latest title but to absolutely bury his in-form opponent in the final, to the point where it was almost a no-contest. He deserves more respect.

Embed from Getty ImagesRON REED has spent more than 50 years as a sportswriter or sports editor, mainly at The Herald and Herald Sun. He has covered just about every sport at local, national and international level, including multiple assignments at the Olympic and Commonwealth games, cricket tours, the Tour de France, America’s Cup yachting, tennis and golf majors and world title fights.

Discussion about this post