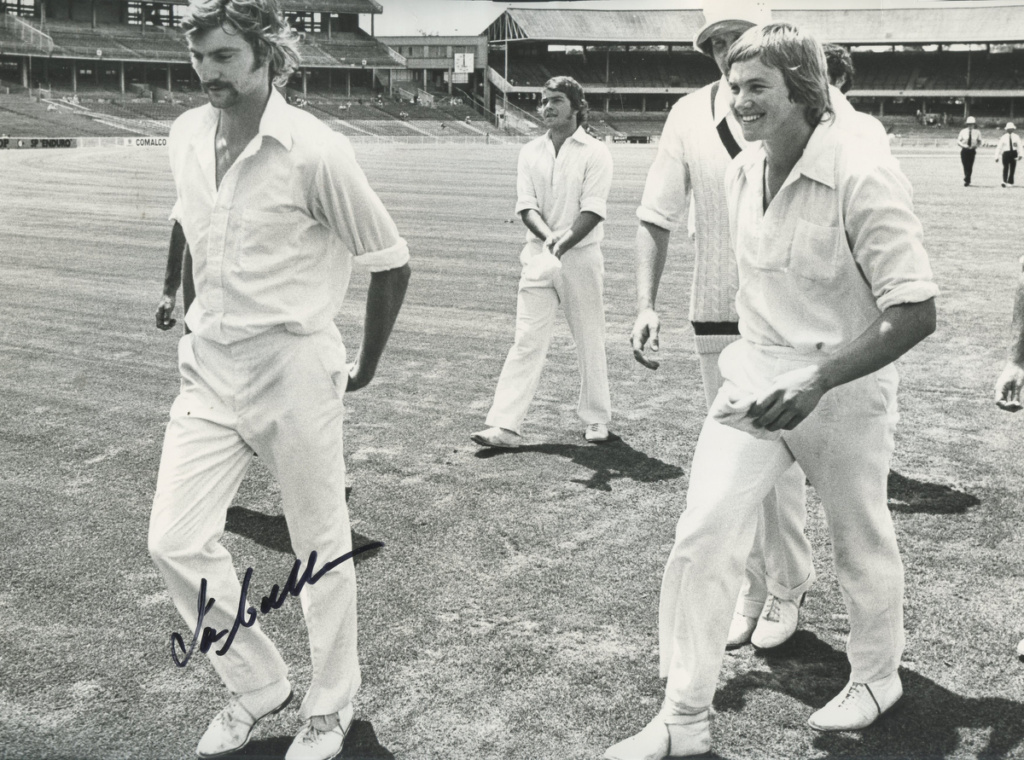

FORTY or so years ago, this weekend, Ian Callen collapsed mid-match during his first Test, the result of an adverse reaction to inoculations ahead of Australia’s 1978 tour of the Caribbean. KEN PIESSE remembers his remarkable effort to rise from his sick bed and play an unforgettable role in what was to be his one and only Test:

SO debilitated was Ian Callen, it was a miracle he was able to get out of his Adelaide hotel bed that morning let alone figure in Australia’s victory against an all-star Indian XI in the series-decider. His supreme effort was crucial — and costly. Never again did he bowl with the same zip or fire. His moment had come and gone.

The Seventies were formidable, arresting times for Australian cricket. In the game’s most momentous decade since the 30s and the emergence of the world-beating “Boy from Bowral” Don Bradman, cricket’s finest became genuine celebrities enjoying a strawberries-and-cream lifestyle thanks to Australia’s richest man, cricket-loving TV tycoon Kerry Packer.

Upset by the austerity of cricket’s rulers who dismissed his bid for exclusive television rights at an infamous meeting at Jolimont in 1976, Packer spent millions bankrolling the first two years of his maverick World Series Cricket movement. He was ready to go again before meeting with Bradman, then in his 70s, who promised him everything he wanted, beginning four decades of Test cricket for Channel Nine.

Those who had figured in the epic Centenary Test in March 1977, received just $1,000 in a match which netted unprecedented gate returns1. During the game, Packer’s chief recruiter Austin Robertson brazenly distributed envelopes to those who had agreed to leave traditional ranks. “Here are your theatre tickets boys,” he said. The envelopes contained sign-on cheques, each for $10,000. Cricket’s head honchos wondered what he was doing there and why he was so friendly with the likes of Dennis Lillee and co. One of the beneficiaries, Kerry O’Keeffe, was working part-time as a brewery carter’s assistant. He didn’t see himself as a regular in Australia’s best XI. The rate of pay at Sheffield Shield level was a miniscule $200, if a match went all four days — less if it didn’t. “I was 28 then and had nothing behind me,” O’Keeffe said. “If my form tailed off, I was back in Saturday afternoon club cricket. I’m glad I signed.” Leading into the 1976-77 international season, the St George wrist spinner had gone unselected for 16 consecutive Tests.

Almost 40 of Australia’s best were swayed by the Packer cheque book. Suddenly they were able to afford new cars and mortgages.

And with new opportunities beckoning at traditional levels, fresh streams of wide-eyed youngsters were promoted into the Test team, many well ahead of their time. While most were to disappear as quickly as they’d arrived, several, like Allan Border, became legends of the game.

Among the 20 elevated into Test ranks for the first time during the tumultuous WSC years were five from Melbourne where club first XIs included the likes of local legends Paul Sheahan, Keith Stackpole, John Scholes, Ian Redpath and Jeff Moss, plus big-name imports Ian Chappell, Ian Botham, Rohan Kanhai and Garry Sobers.

Ian Callen, a rangy teenage paceman from Heathmont, had played men’s cricket on the mats and won Australian Under 21 selection after one Cricket Union of Victoria carnival.

Totally undaunted by names and reputations, at Carlton’s practices he bowled bouncers aplenty, sparing no-one, even the club’s two legends, captain-coach Stackpole and Scholes. Rarely were they delivered from the full 22 yards. He answered to the nickname “Mad dog” — the result of a prank in a pre-season camp in Shepparton when he grabbed the beer gun from a senior teammate and promptly squirted him between the eyes. “I knew you were going to do that, you bloody Mad dog,’ said an aggrieved Geoff Measom.

With a very high, erect action, similar to Josh Hazlewood, he could bowl a “heavy” ball and seam it both ways at pace. Few were to be fast tracked faster into representative ranks. In 1974-75 Callen started in Carlton’s third XI. He was 18 and 188cm (6ft 2in) but played at a stripling’s weight of 75kg (11st 11lb). Four years later he was in the Test team.

Victoria’s long-time coach the legendary English express Frank “Typhoon” Tyson was a fan of Callen’s easy-going attitude and sense of humor. He also liked his rhythmic approach and his acceleration into the crease. Like the great Australian of the 50s Alan Davidson, he ran from 15 paces. His arm was high and the seam upright. He could be seriously sharp. “Importantly,” said Callen, “Frank believed in me. Most of the time as a young player coming through though you were left to your own devices. There wasn’t as much support available as there is now.”

Callen had first announced himself as a bowler of the future when representing the Victorian Colts against NSW Colts in sweltering heat at the Sydney Cricket Ground late in 1975. “It was 40 degrees in the shade and John Dyson (for NSW) made 170. Overnight I had none for 80-odd from 14 overs after my first four cost almost 50. I was frothing at the mouth coming off. It was just so hot. There was no such thing as a heat policy back then. But I ended up taking five-for. One of them was a young fella by the name of Border. Think it was his first rep game. A few people sat up and take some notice then.”

Within 12 months Callen was opening Victoria’s bowling and at the end of the 1977-78 summer was named in Australia’s XI for the deciding Test against India.

Despite all the hoopla about Packer and the big names he had attracted to World Series Cricket, traditional cricket maintained peak ratings and a loyal following. Purists were uncomfortable at the new professionalism in the game. They mistrusted Packer and regarded his men as mercenaries.

Bobby Simpson had been recalled as Test captain after a decade playing exclusively on Saturday afternoons. As part of the terms agreed at a September luncheon with the all-powerful Sir Donald Bradman, Simpson, 41, also was to captain NSW and choose where he would bat. The Sheffield Shield’s gala match each season was the Christmas “test” hosted by Victoria against arch rivals NSW. Sent in to bat on a near grassless MCG wicket on the Friday, NSW was comfortably placed at 2-100 shortly after lunch before Callen, in an electrifying spell, took 6-16 to blast the blue-baggers out for under 200. A high-speed off-cutter jagged back at Simpson, catching him in front first ball. He was lbw. It was a peach of a delivery. Only minutes earlier the small crowdhad warmly applauded Simpson’s entry. Ten years earlier, in his previous appearance in Melbourne, he’d made a century and passed 4,000 Test runs. He was a legend of the game. As he eyed Simpson from the top of his run-up Callen muttered to himself: “You won’t see this.”

Struck on the crease line, Simpson quickly looked up at umpire Kevin Carmody. “He was trying to give him the message: ‘Don’t you dare give me out,’” said Callen, “but up went Kevin’s finger. It was a sweet moment for me.”

Callen deserved an immediate Test call-up, but Australia’s selectors Phil Ridings, Neil Harvey and Sam Loxton had already released the Test XII for the back-to-back Tests, in Melbourne from December 30 and Sydney from January 7. The Indians were a seasoned outfit and recorded back-to-back wins with their batsmen in improved form and spin bowlers supreme. The series was suddenly all-square at 2-2 approaching the final Test, in Adelaide. A sixth day was allocated to make sure of a result.

After seeing their team humbled in Sydney, the Australian selectors made five changes, Callen one of four debutants, along with openers Rick Darling and Graeme Wood and the West Australian bowling allrounder Bruce Yardley, who had reinvented himself as a finger spinner after years of being overshadowed by local swing king Ian Brayshaw. All were also named in the soon-to-follow tour of the West Indies.

Callen, 22, had played just a dozen Shield games. He didn’t care that the who’s who of Australia’s best cricketers were playing in a rival competition. He was on the Adelaide Oval, representing his country. “I was just so happy to be playing. It was a dream come true,” he said.

With his “lucky” American one-dollar coin, Simpson again won the toss, a pivotal moment. He reckoned he had his best-balanced XI of the summer. Two left-handers (Wood and the recalled Graham Yallop) in the top six reduced the potency of the Indian spinners, who had mowed through the Australians in the two previous Tests. With Kim Hughes 12th man, Yardley was in the XI and immediately went to the nets for a celebratory bowl only for Callen to power a straight drive so hard it thudded into Yardley’s bowling hand, breaking the skin of his little finger. Jeff Thomson pulled the finger straight again and Yardley was cleared to play, but only after the Indians agreed he could bowl with his mangled finger strapped.

Australia started with 505, Yallop and Simpson scoring centuries. Even into his 40s, Simpson was still formidable, especially against the spinners as he advanced yards down the wicket to meet the ball on the half volley. The pitch was ultra-true. Even the tail prospered, Thomson and Callen, in at No.11, adding 47 for the last wicket, the Australians batting into a fifth session.

Callen was used at first change within the first half an hour when Thomson tweaked a hamstring and limped off halfway through his fourth over. He was unable to bowl for the rest of the match.

Standing at the top of his run up for the first time, Callen was so struck by nerves he wondered how he possibly could hit even the pitch — let alone focus on the top of off stump. “It took me a while to find my feet,” he said.

He loved Simpson’s involvement and encouragement, his guidance and especially the confidence he had in him. “‘You’re here because you deserve to be here,’ he’d say to me. ‘You can do this. C’mon.’”

It was a magnificent batting wicket with true bounce and little or none of the sideways movement he had enjoyed on his home wickets in Melbourne.

He took six wickets for the game from 55 eight-ball overs, a Siddle-like performance. He also made 22 not out and four not out as Simpson’s young Australians won the thrilling deciding Test and the series 3-2.

“I fractured a vertebra from over-straining in that game and never bowled as fast again,” Callen said.

“I started feeling crook during the match. Someone said it was yellow fever, but I wasn’t going to withdraw. This was my opportunity. They gave me six injections in my left arm and on I played.”

Callen took three for 83 and three for 108, bowling first change behind Thomson and Wayne Clark in the first innings and opening with Clark in the second after Thomson broke down.

At the height of his injury and illness concerns, his pace tailed off so badly that Simpson approached, asking him if he wanted wicketkeeper Steve Rixon to stand up over the stumps. “Bobby might have thought I wasn’t getting them through as fast as I might,” said Callen. “His words got the desired result.”

His victims in his one-off Test included Vishwanath, Vengsarkar and Gavaskar, three of India’s finest.

The game carried into a sixth day, India starting at 6-363, requiring another 129. “It seemed an impossible task,” said Simpson, “even though we were a bowler short. But they kept on coming at us.”

After three military-medium overs from Clark, also struggling with a back strain, Callen took the second new ball with India 7-415 and substitute fieldsman Hughes took a fine gully catch from Callen’s bowling. Soon afterwards Callen dismissed Bishen Bedi. “It was a brilliant finish to a magnificent season,” said Simpson. “Callen responded magnificently on that last day, especially after I’d called for the doctor to come to our hotel and see him at 3 a.m. that very morning. Time and time again he caught the edge of the bat and watched as the ball went frustratingly wide of the field. Taking two of the last four wickets was his just reward.”

Despite touring the West Indies in 1978 and Pakistan in 1982-83, Callen did not play another international. He even took himself off to South Africa in 1985-86 where he returned to first-class cricket after recovering from knee surgery. His club side won the Boland Club Championship and Boland won South Africa’s Division Two Castle Bowl title. So good was his form that he was almost called into the rebel tour by Kim Hughes’ Australians.

A journeyman cricketer who loved his mates and regularly upset officialdom, Callen answers more to “Mad dog” than he does to Ian.

He loved his time playing alongside mates such as Max Walker, Richie Robinson, Trevor Laughlin and Paul Hibbert, who all backed him unconditionally. “When they were all dropped it took a lot of fun out of it for me. I didn’t want to play anymore,” he said.

Tall, spindly and susceptible to injury, Callen had an enviable strike-rate with Victoria of 49 balls per wicket. Leading into his Test call-up, in five matches in 1976-77 he took 31 wickets. He had a lovely side-on, rocking action, a late out-swinger and a leg-cutter.

- Edited excerpts from Ken Piesse’s new book ONE TEST WONDERS. It will be available later in the year from http://cricketbooks.com.au

KEN PIESSE has covered cricket and football for more than 30 years in Melbourne. Despite that setback, Ken has written, published and edited 86 books on cricket and AFL football to become Australian sport’s most prolific author.

His latest cricket book is David Warner, The Bull, Daring to be Different with Wilkinson Publishing, out now

www.cricketbooks.com.au

Discussion about this post