HOW UNLUCKY can you be? BRIAN MELDRUM looks back on two controversial finishes to the Caulfield Guineas which were fought out in the stewards’ room:

BRIAN RALPH will be in Alice Springs when they run Saturday’s Caulfield Guineas at Caulfield, but you can bet he’ll be giving it some thought.

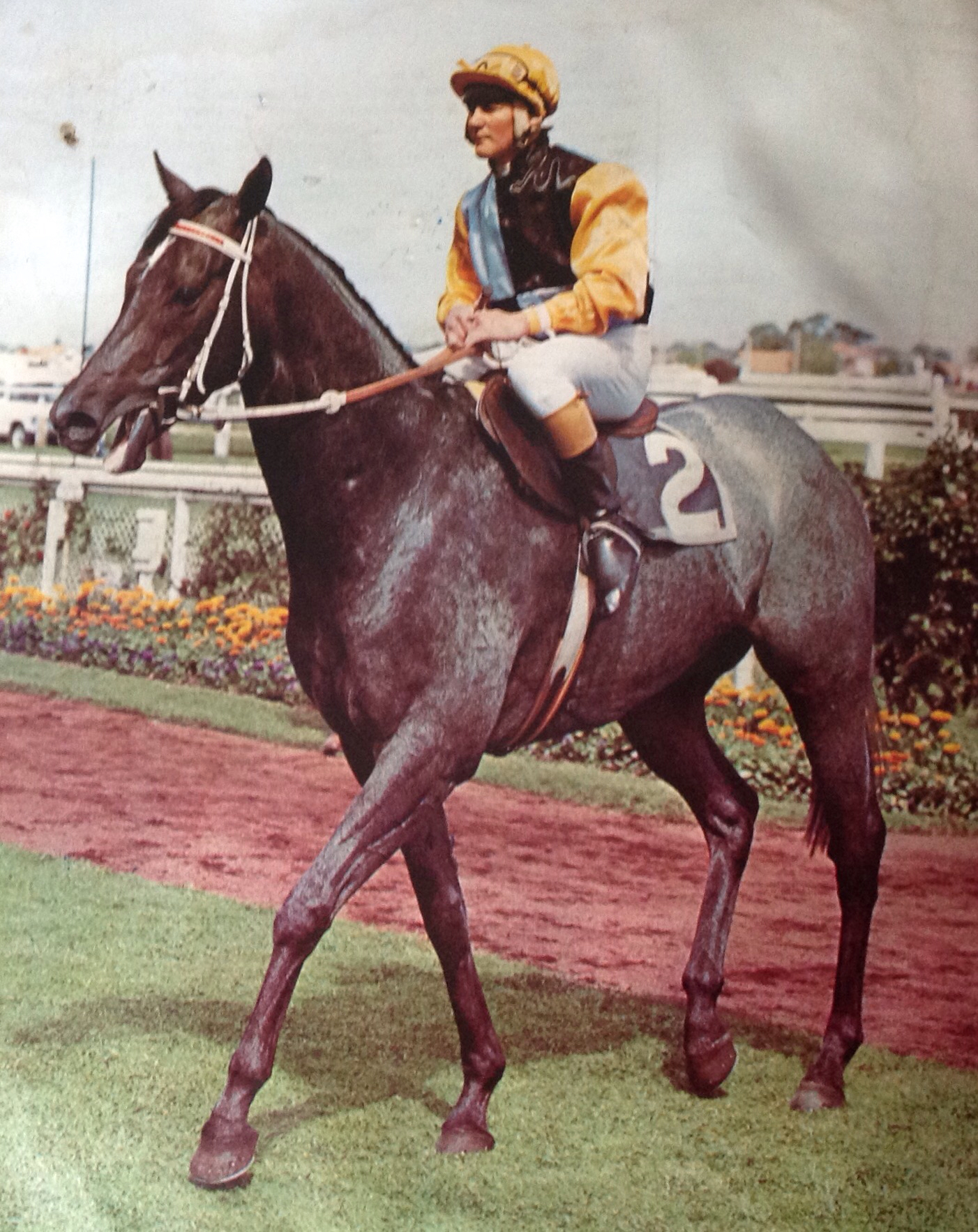

Not so much Saturday’s race, but the 1978 Caulfield Guineas, in which the former trainer saddled up the classy, gunmetal grey colt Karaman.

Ralph will remember the field coming around the home turn, and he’ll picture young rider Garry Murphy riding Karaman, having his main rival, Manikato, pocketed with nowhere to go.

No doubt he’ll probably flinch when he recalls the moment Gary Willetts, on Manikato, slammed Karaman out of the way and went on to win the race, and then survive a protest most thought would be upheld.

And he’ll shake his head yet again in the knowledge that Willetts later that day was suspended for three months after being found guilty of foul riding, a charge which on appeal was reduced to improper riding.

But perhaps his most vivid memory will be of attending the Cox Plate meeting two weeks later – Karaman ran third in the weight-for-age classic behind So Called – and along with the colt’s owner, the one-time Lord Mayor of Melbourne, Sir Maurice Nathan, being invited into the stewards’ room to view the film of the Caulfield Guineas.

“Because of some sort of technical problem the stewards film was of no use to them on Guineas day, so they only went on what they saw from the stewards’ towers,” Ralph said.

“We went in and sat down, and watched the film, and no one said anything. When it was finished Sir Maurice and I thanked them for letting us see it, and headed for the door. But as we got to it, a voice said, ‘Unfair, wasn’t it!’”

Ralph is almost certain the comment came from the then chairman of stewards, Jim Ahern, who suffered a heart attack the following April and handed the reins to Pat Lalor after 19 years as the chief steward. “We didn’t say anything. What was the point? It was too late then.”

It was a bitter blow for all of Karaman’s connections, but probably felt more by the trainer and the jockey. Ralph was working hard to establish himself in the top echelon of Melbourne trainers, and Murphy was being talked about as a top jockey in the making.

Murphy, who’d come down to Melbourne from Ballarat to serve the last year of his apprenticeship with Ralph and had continued riding for the stable, in the start before the Guineas had piloted Karaman to win the Moonee Valley Stakes.

“Roy Higgins rode him when he finished second to Manikato in the Ascot Vale Stakes, but for some reason couldn’t ride him at Moonee Valley, so Brian put me on,” Murphy recalls. “He stuck with me at Caulfield.”

In the aftermath of the Guineas, Ralph came in for some criticism for putting a relatively inexperienced jockey on Karaman, but according to Murphy never once did he use that as an excuse for what happened.

And why would he? Murphy had produced a great tactical ride to have the favourite on his inside, locked away on the fence with seemingly nowhere to go. How long he could have held him there, had not Willetts barged his way out, is anyone’s guess. But given the winnng margin was only a length and three quarters, and that Karaman was badly hampered by the winner, then no one can be sure the grey wouldn’t have won. Apart from the stewards, that is!

Murphy was shocked by the decision to dismiss the protest, but that was nothing compared to how he felt exactly a year later, after the running of the 1979 Caulfield Guineas.

He was on a colt named Bold Diplomat for Caulfield trainer, Kel Chapman, and rode a beautiful race to be a clear winner. Halfway down the straight his horse hung in across the runnner-up, Runaway Kid, who suffered what appeared to be a fairly mild check.

Most racegoers were somewhat surprised when Runaway Kid’s jockey, Pat Hyland, fired in a protest against the winner, and it’s fair to say they were stunned when it was upheld. But not half as stunned as Murphy.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Murphy says. “I won by two lengths, which was a bigger margin than I’d been beaten the year before on Karaman.”

Understandably Murphy was still smarting from the Karaman defeat when he was hit with the drama surrounding Bold Diplomat’s “win”, and it took him a long time to recover from these huge disappoinments.

“It took me about four years to finally move on,” he said. “I felt very bitter.” In particular he developed what he describes as a “shocking” attitude towards the stewards, and as a result often found himself on the wrong side of them.

In the early 1980s, when multiple suspensions threatened to undermine his position as stable jockey to ace Flemington trainer Tommy Hughes, Murphy heeded his boss’s advice and had a meeting with Lalor, who’d presided over the protest against Bold Diplomat.

He says he didn’t get much of an explanation from Lalor about the protest decision, but says just having the meeting “made me feel a bit better”, and he went on to have a long and successful career in the saddle.

So, what did the “experts” make of the two protest decisions?

In regards to the Karaman-Manikato incident opinion seemed to favour the winner, the belief being that he would have eventually found room in time to get out and win. Against that, though, is the fact the stewards saw fit to charge Willetts with foul riding, and there were those who believed that alone should have been reason enough to amend the result.

In regards to the protest against Bod Diplomat, most were left scratching their heads. Sure there was interference, but very few people reckoned it had cost Hyland’s mount the two lengths by which he was beaten, apart from those who’d backed Runaway Kid. Oh, and the stewards.

Brian Meldrum has been a racing journalist for more than 47 years, and is a former Managing Editor - Racing, at the Herald Sun.

Discussion about this post