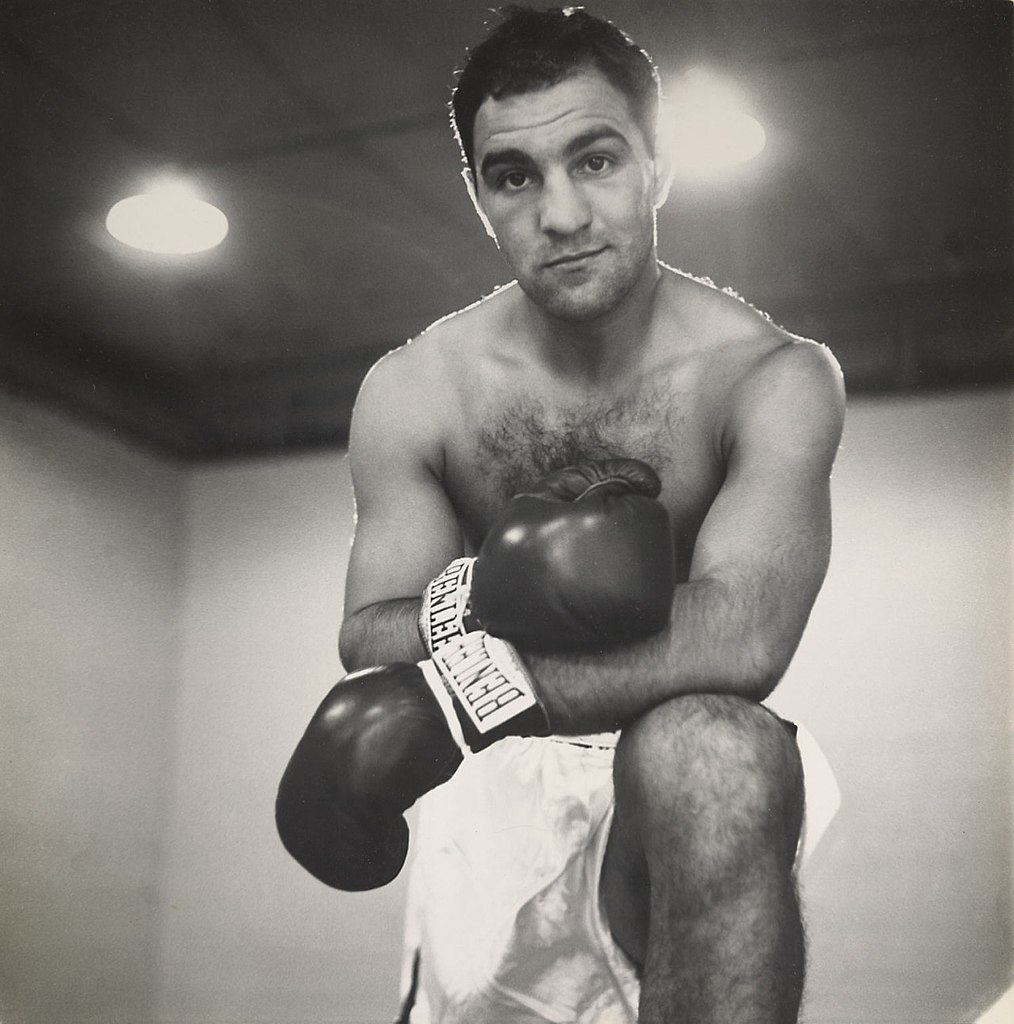

FLOYD MAYWEATHER took more than one title when he stopped Conor McGregor in Vegas, He also knocked the great Rocky Marciano off his perch, as PETER COSTER reports:

IN THE AFTERMATH of a fight that was a multi-million-dollar marketing extravaganza that became a slightly serious contest, Floyd Mayweather Jnr, whose father was also a world champion, extended his unbeaten record to 50.

What was largely lost in the hubris and the hype was the name of the undefeated world champion whose record “Money” Mayweather, had just eclipsed.

Rocky Marciano’s real name was Rocco Francis Marchegiano, but try pronouncing that with a mouth guard. Muhammad Ali, who more often badmouthed his opponents, called him “Champ” when they fought in 1969. It was in a gym with black curtains instead of a crowd, in a fantasy fight determined by a computer.

Ali had been stripped of his title after refusing to answer a call-up to the Vietnam war as a conscientious objector. He needed the money. Marciano, who could not get enough of it, had not fought for 13 years and stepped into the ring wearing a toupee that Ali flicked off.

“Cut, cut the camera!” roared Rocky. “Watch the piece!”

Ali claimed flicking the toupee off was an accident. His trainer, Angelo Dundee, who knew the guy in New York who made Marciano’s toupees, said it looked “like a dead cat” and yelled, “Rocky, watch out! The thing might get up and run away.”

Like too many fights, the fix was in and the computer claimed Marciano knocked out the Louisville Lip in the 13th of the 15 rounds then fought for a world championship.

Yeah, tell me another one, says this writer, who was too young to see Marciano fight in the 1950s, but saw the Brockton Blockbuster on newsreels. Marciano was so short it was doubtful he would have reached Ali’s chin. At 5ft 10in to Ali’s 6ft 3in, the Rock would have relied on his walk-up style to engage Ali. He was a swarmer who knew no other way.

The great sports reporter, Red Smith, wrote that “fear wasn’t in his vocabulary and pain had no meaning”.

Associated Press reporter Whitney Martin wrote that Marciano’s footwork consisted of “moving forward in a direct line to a point where he was within cannonading range”.

The cannon balls were in either hand, on arms so short he had to deliver the blows with his head often resting on the chest of an opponent.

By the time Marciano stepped into the ring against Ali, he was 45, balding under the rug and had not fought for 13 years, and was soon to die in an aircraft accident.

He had spent his time since retirement exercising with women other than his wife but got back into training for the fantasy fight. It was the greater vanity.

What was a reverse reflection on Marciano as world champion was written by Red Smith after Marciano’s victory over Joe Louis.

The Brown Bomber, another champion whose name would mean nothing to the millions of fans who watched the Mayfield versus McGregor marketing exercise.

Louis was the first black heavyweight champion since Jack Johnson, who at just over 6ft, towered over Tommy Burns, who was even shorter at 5ft 7in than Marciano.

My grandfather was one of 20,000 fans who saw the fight, appropriately on Boxing Day in 1908, which led to black men dominating the heavyweight division. The Great White Hope was the tag for a string of failed contenders.

Marciano proved a brutal exception. Joe Louis had been beaten only three times in his illustrious career in this bloodiest of sports; unless you consider a bullfight and the goring of a matador worse. There is death in the corrida as well as the ring.

Newspaper reporters then rather than now had a relationship with fighters that saw them admitted to dressing rooms after a defeat to hear the anguished warrior’s words as well as those of the victor.

The style of American boxing prose, even the comments of the combatants, is more Marciano than Muhammad Ali.

Heavyweight champ Archie Moore said of Marciano: “Rocky didn’t know enough boxing to know what a feint was. He never tried to outguess you. He just kept trying to knock your brains out.”

So it was that on a night in 1951, Joe Louis, who had been knocked out by Hitler’s champion Max Schmeling (whom he later humiliated in a bout in which the German screamed at the force of the Brown Bomber’s blows) found himself the vanquished.

Red Smith had literacy in his repertoire as well as punishing prose. Joe was lying on a rubbing table, his right ear on a folded towel and his left hand in a bucket of ice. “This was an hour before midnight of October 26, 1951,” wrote Smith, and the “evening of a day that dawned July 4, 1934, when Joe Louis became a professional fistfighter and knocked out Jack Kracken in Chicago for a 50-dollar purse. The night was a long time on the way, but it had to come.”

Smith waxed eloquent, as the pugs, trainers and money men who read his columns, might have said.

“Now the punch that was launched 17 years ago had landed. A young man, Rocky Marciano, had knocked the old man out. The story was ended.”

The newspaper men were crouching, “kneeling on the floor like supplicants to hear him”.

“Did age count tonight, Joe?” the Bomber was asked.

“Ugh,” he said and bobbed his head.

“This kid knocked me out with what? Two punches? Schmeling knocked me out with, musta been a hundred punches. But I was 22 years old. You can take more then than later on.”

Ray Arcel, who for years had trained opponents demolished by Joe and “in a decade-and-a-half had dug tons of inert meat out of the resin”, was asked how he felt.

“I felt very bad,” Arcel responded gravely.

“It wasn’t necessary to ask how Marciano felt,” wrote Smith. “It will be said it wouldn’t have been like this with the Louis of 10 years ago, but that would not be a surprisingly bright thing to say because this isn’t 10 years ago.”

The Joe Louis of October 26, 1951, “couldn’t whip Rocky Marciano,” said Smith “and that was the only Joe Louis who was in the ring at Madison Square Garden that night. An old man’s dream had ended, but the place for old men to dream is beside the fire.”

As a troubled aficionado of this sport, I was at the Pavilion in Melbourne after “Wild Will” Tomlinson won a decision over a Mexican on a night when the lights went out in the eighth round.

Tomlinson, who was making his first defence of his world super featherweight title, was declared the winner when the lights failed to come back on.

We got in a huddle to hear Tomlinson’s words and the opinion of the American referee, slick-haired Steve Smoger, who came over to conduct proceedings.

A couple of us then piled into a small car in which we hitched a ride. One of the boxers on the card that night ran alongside us, rapping on the window.

He wanted to go home, but Howard Leigh, who was the ring announcer and whose car it was, said there wasn’t room and he had to get “these newspapermen back to file by deadline”.

It felt as if it were 1951 and Red Smith was there with us after Rocky Marciano had sent Joe Louis on a road that would end with him sitting in a chair at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas; earning a few miserable dollars signing autographs as a “greeter”.

Like Red Smith, whose collection of columns had been given to me in Los Angeles by Peter McFarline, a mate and a peerless sports writer, I foresaw that Wild Will’s lights would be turned off.

There is much sentimentality in boxing but also evident truth. Tomlinson hung up his gloves last year, his courage unquestioned after taking too much punishment in this most painful of pursuits.

That decision made him a winner.

PETER COSTER is a former editor and foreign correspondent who has covered a range of international sports, including world championship fights and the Olympic Games.

Discussion about this post